Learn about the potential for cell transplantation for the treatment of the advanced form of dry age-related macular degeneration, with some very important information about clinical trials.

What is Geographic Atrophy?

In patients with advanced dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD), also called geographic atrophy (GA), important cells in the center of the retina die. Geographic atrophy refers to regions of the retina where cells have wasted away and died, and it may look like a map to the doctor who is examining the retina, hence the term “geographic.” This cell death is usually limited to the region in the center of the retina, called the macula, enabling patients to keep their peripheral vision. Unfortunately, the loss of central vision makes it impossible to drive and very difficult to read or recognize faces.

Recently, there has been much interest in cell transplantation in medicine in general, and specifically for the treatment of GA. In patients with GA, the area of dead cells expands over several years, suggesting that a stem cell transplant near the edge of the dead, atrophied region could prevent the expansion of atrophy.

Replacing RPE Cells to Save Sight

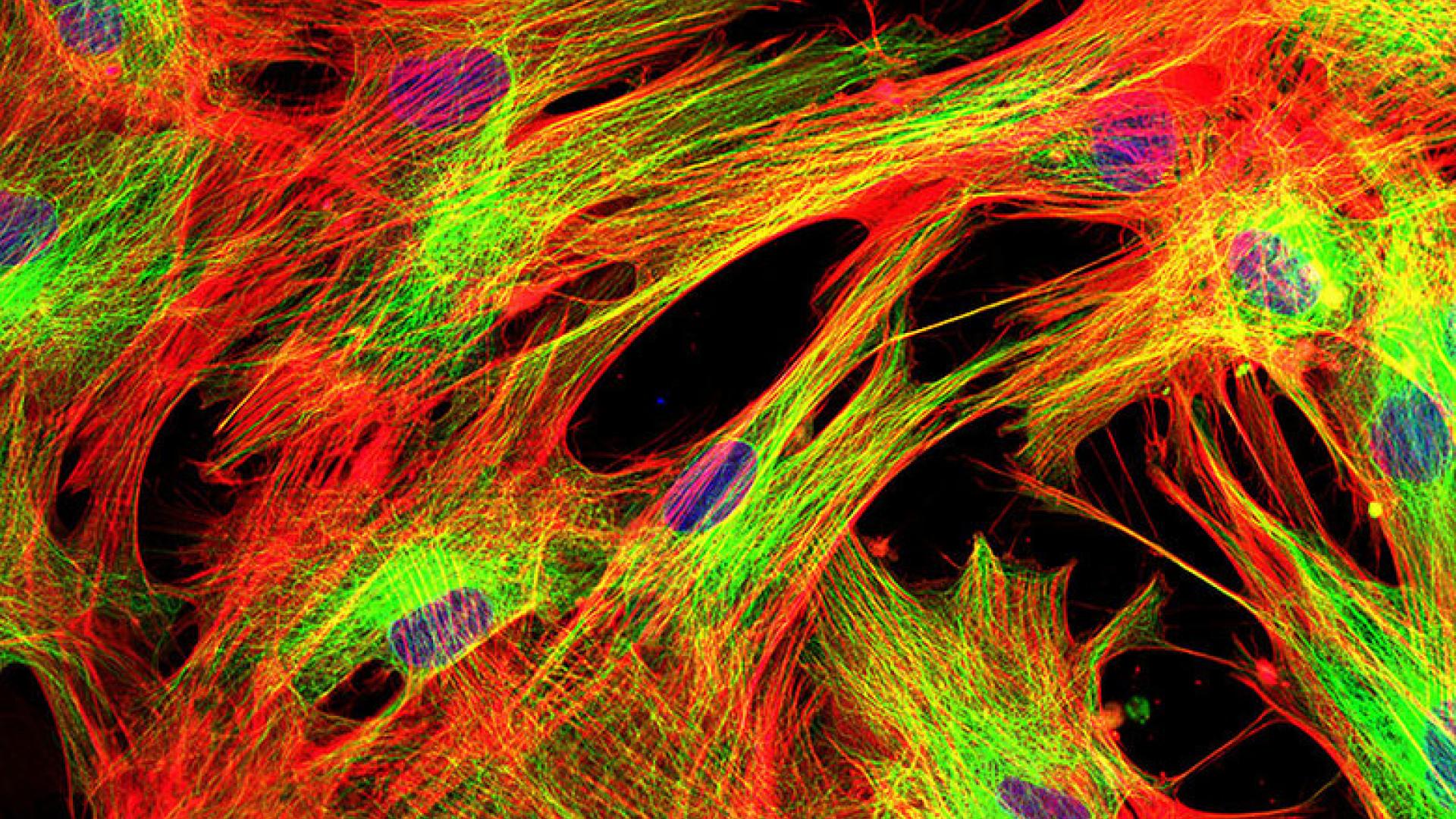

Further, two main cell types die in GA. One is the light-sensing photoreceptors (rods and cones), and the other is the retinal pigment epithelial cells (RPE) that support the photoreceptors. Sometimes, at the edge, or even within, the atrophic region, RPE cells die, but photoreceptors survive, at least for a period of time, suggesting that replacing the missing RPE cells could restore the function of photoreceptors and prevent or slow expansion of the atrophy.

Replacing RPE cells should be easier than replacing photoreceptors because photoreceptors need to make specific electrical connections with other neurons, and this is difficult to accomplish in an adult retina. In mice, transplanted RPE cells have been shown capable of supporting photoreceptor survival and function.

Several sources of RPE cells, including eyes donated for medical research, and RPE cells derived from the skin of the recipient have been used in early stage human clinical trials with a few participants in each trial.

In the latter approach, fibroblast cells* from a skin biopsy are grown in a plastic dish, and then genetically modified to become stem cells (which are capable of many cell divisions). The fibroblasts are then coaxed with protein growth factors to become RPE cells.

The RPE cells are then delivered into the appropriate position, just underneath the retina, by a retinal surgeon. The procedure is performed using local anesthesia. In some cases, cells floating in fluid are injected into the eye. In others, the cells are grown as a sheet attached to a thin membrane, which is then positioned under the retina.

Cell Therapy Clinical Trials for Macular Degeneration

Among the RPE transplantation trials conducted thus far for patients with GA, Stargardt’s disease, or wet AMD (who didn’t respond well to anti-VEGF injections), the results have shown pretty good indications of safety. No tumors have developed in the eye, which is a concern when cells capable of dividing are introduced into the eye. In a few cases, cells have grown on the surface of the retina, not forming a tumor, but producing a thin membrane that wrinkled the retina and needed to be surgically removed. In a few other cases, a retinal detachment occurred as a complication of the surgical procedure and required additional surgery to repair.

In two of the larger GA trials, those by Schwartz et al. and Kashani et al., there is evidence that some of the transplanted RPE cells survived, and there was a hint of improved vision and/or photoreceptor structure in a few patients.

Important Clinical Trial Information

Patients with GA who might be interested in enrolling in an RPE transplantation clinical trial should ask their ophthalmologist about their eligibility and the current availability of trials. Under no circumstances should patients have cell transplantation or injection outside the protections of a clinical trial registered on clinicaltrials.gov or Antidote. Recently, stem cell injections into the eye, offered by a clinic but not part of a registered clinical trial, resulted in catastrophic vision loss due to the lack of proper regulatory approval. For more information on this issue, visit here.

Summary

RPE transplantation is a promising area of research that has produced some glimmers of success but requires further optimization in the laboratory and within clinical trials.

About BrightFocus Foundation

BrightFocus Foundation is a premier global nonprofit funder of research to defeat Alzheimer’s, macular degeneration, and glaucoma. Since its inception more than 50 years ago, BrightFocus and its flagship research programs—Alzheimer’s Disease Research, Macular Degeneration Research, and National Glaucoma Research—has awarded more than $300 million in research grants to scientists around the world, catalyzing thousands of scientific breakthroughs, life-enhancing treatments, and diagnostic tools. We also share the latest research findings, expert information, and resources to empower the millions impacted by these devastating diseases. Learn more at brightfocus.org.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is a public service of BrightFocus Foundation and is not intended to constitute medical advice. Please consult your physician for personalized medical, dietary, and/or exercise advice. Any medications or supplements should only be taken under medical supervision. BrightFocus Foundation does not endorse any medical products or therapies.

- Treatments