Learn about the key differences between the early- and late-onset forms of Alzheimer’s disease.

Alice glanced at her husband with an expression that mixed love with worry. “This all started about a year ago,” she said, “just after Ed’s 58th birthday. At first, all we noticed was that he was speaking more slowly and sometimes he couldn’t think of the word he wanted. His memory didn’t seem too bad then, but it’s gotten worse since. Now he seems to have trouble understanding anything more complicated than a simple sentence. He had to leave work, and we’re worried about the future. He knows things are not right, and we feel very alone with this. Ed’s mother developed dementia in her 60s, and it was awful for her and her family. We worry, too, about our children. Are they going to get this?”

Ed and Alice visited their primary care physician with their concerns and were told that Ed’s condition did not sound like Alzheimer’s disease (AD). “He’s too young for that,” said Dr. Kent. Just to be complete, Dr. Kent asked Ed to remember three words. When Ed was asked to repeat them after 3 minutes, he did so with little difficulty. “That doesn’t seem like Alzheimer’s disease,” said Dr. Kent.

Dr. Kent was correct, since 90 to 95 percent of AD cases occur in people of age 65 years or older. Furthermore, early in its course, AD typically attacks memory of past personal experiences that occurred at a particular place and time, which is called episodic memory. Difficulty with language could suggest a stroke, a different type of dementia, or some other condition. But, as is often a surprise to many clinicians’ and patients, some AD cases actually begin earlier as it did with Ed, whose subsequent amyloid PET scan showed that his brain had accumulated the amyloid plaques linked with AD.

*The names and details in this story are composite and fictitious. They do not identify specific individuals.

Early- and Late-Onset Alzheimer’s: How do they Differ?

Early-onset Alzheimer’s disease (EOAD) affects people younger than age 65, and is a less common form of dementia.

EOAD, which is thought to affect between 220,000 and 640,000 Americans, begins between age 45 and 64. It looks different than late-onset AD, and it has different consequences because it arrives during the prime years of adulthood. That may be why the delay between symptom onset and diagnosis is greater for EOAD than for AD that manifests in older individuals. However, early recognition is especially important in cases of EOAD.

The symptoms of EOAD can be similar to the late-onset form of the disease. These symptoms include:

- Changes in personality

- Impaired gait or movement

- Language difficulties

- Low energy

- Memory loss

- Mood swings

- Problems with attention and orientation

- Problems with simple mathematical tasks

However, there are some key differences between EOAD and typical, late-onset AD:

- The majority of EOAD does not run in families. However, some cases of EOAD have a stronger pattern of genetic inheritance than late-onset AD. There is likely to be a parent who developed AD at an age less than 65 in as many as 13 percent of EOAD cases. In these families, there may be a gene mutation that is passed along as an autosomal dominant trait, which means that it affects half of the offspring of the person with this form of AD.

- Memory loss may develop later in the course of the disease and be less prominent in people with EOAD than in those with typical later-onset AD.

Dr. Mario F. Mendez (see Further Reading below) describes how EOAD can present atypically, and he groups these together as “Type 2 AD”:

- Some people with EOAD show difficulty finding words, which could look like a condition called aphasia (the loss of ability to understand or express speech) or variant of frontotemporal dementia;

- Posterior cortical atrophy, which is sometimes another variant of EOAD, is recognized by the occurrence of difficulty reading (alexia) and other visual complaints despite apparently normal functioning of the eyes. The problem is in the brain, specifically in the areas that process and make sense of the sensory information that the eyes deliver to the brain;

- Another EOAD syndrome, called progressive ideomotor apraxia, can cause a person to have trouble demonstrating learned movements of the limbs, both when asked to do so and when asked to imitate the physician’s limb movements;

- Frontal variant AD (behavioral-dysexecutive AD) can confuse clinicians because it presents with apathy (a lack of concern, interest, enthusiasm, or emotion) that would suggest depression but the response to antidepressant treatment might be very limited.

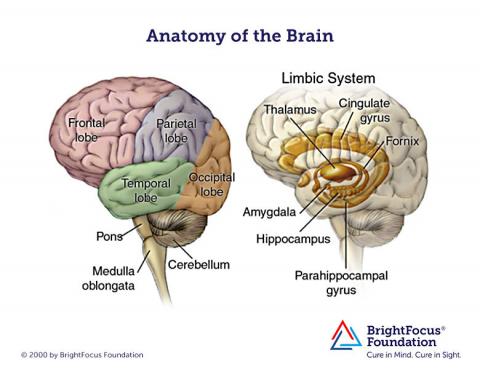

MRI brain images of people with EOAD can look a little different than the images for typical AD. For example, shrinkage of the hippocampi and temporal lobes is less, and shrinkage of the parietal lobes is more prominent, with EOAD. Also, changes in white matter (the nerve fibers that connect parts of the brain and spinal cord) may be more significant in MRI brain images in people with EOAD.

Treatment Options

As with later-onset AD, no specific medication will cure or even reverse the disease, but medications such as Aricept® (donepezil) and Namenda® (memantine) can nonetheless reduce symptoms in some people. Amyloid PET scanning may help with the differential diagnosis in some situations if that is available. Genetic tests will identify the small number of individuals with the form of the disease than can be passed along to their children, and that is important for assisting with genetic counseling.

Interventions, which should take place once the diagnosis is well-established, can include support groups for the patient and help for family members. With an adult in his or her 50s, discussion often includes counseling regarding how to modify or exit from employment. Patients and families can be guided toward available resources, support groups, and services for EOAD patients and their caregivers. Given the early-onset and projected survival time, some patients will choose to participate in a clinical trial. That may offer the patient and care system some hope while contributing to general knowledge that will help many others as well.

About BrightFocus Foundation

BrightFocus Foundation is a premier global nonprofit funder of research to defeat Alzheimer’s, macular degeneration, and glaucoma. Since its inception more than 50 years ago, BrightFocus and its flagship research programs—Alzheimer’s Disease Research, Macular Degeneration Research, and National Glaucoma Research—has awarded more than $300 million in research grants to scientists around the world, catalyzing thousands of scientific breakthroughs, life-enhancing treatments, and diagnostic tools. We also share the latest research findings, expert information, and resources to empower the millions impacted by these devastating diseases. Learn more at brightfocus.org.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is a public service of BrightFocus Foundation and is not intended to constitute medical advice. Please consult your physician for personalized medical, dietary, and/or exercise advice. Any medications or supplements should only be taken under medical supervision. BrightFocus Foundation does not endorse any medical products or therapies.

- Brain Health