When you picture someone living with Alzheimer’s disease, who do you see? If we went by the stats, you would picture a woman over the age of 65 who receives her Alzheimer’s diagnosis after loved ones took her to the doctor with concerns about lapses in memory.

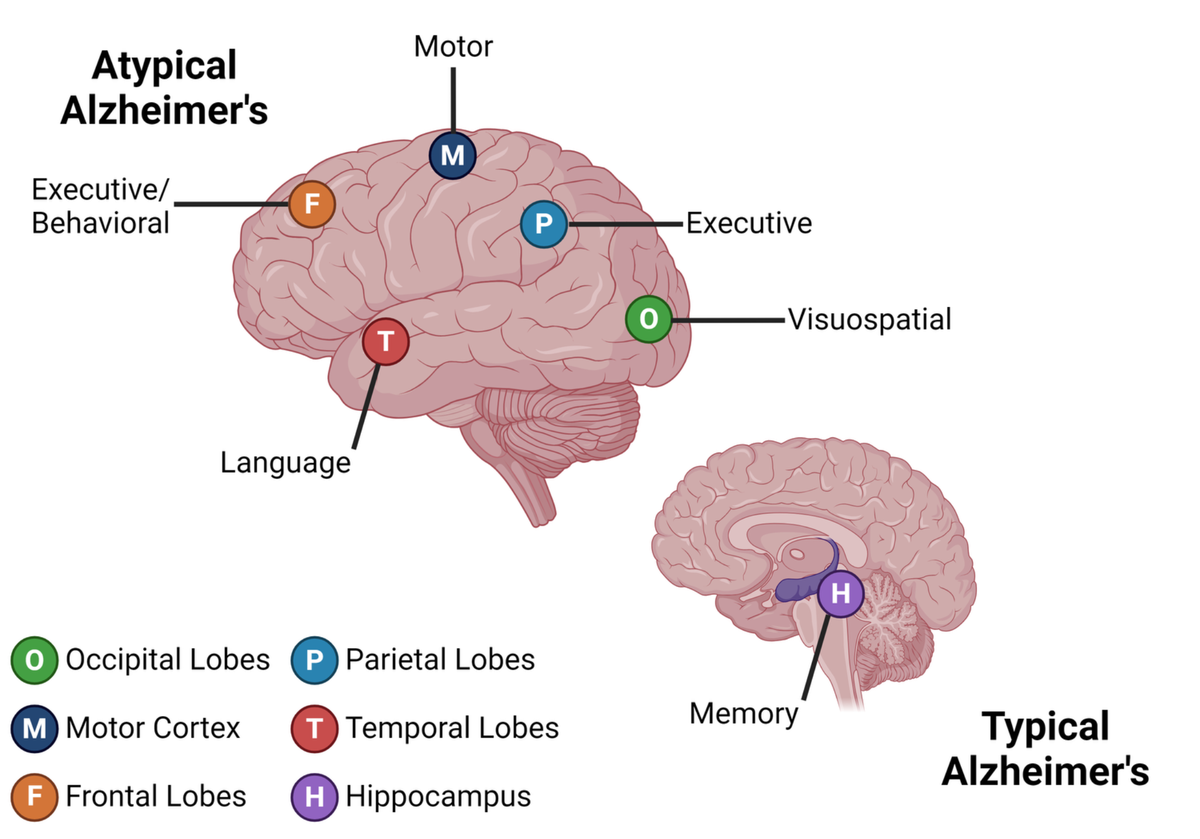

If the person who appears in the doctor’s office is young, Alzheimer’s may not be the first consideration. Especially if the individual isn’t complaining of memory problems, but instead difficulties with vision, language, motor skills, or personality changes. Yet for nearly one-third of young-onset Alzheimer’s cases, this is just the scenario.

These “non-memory” forms, collectively called atypical Alzheimer’s, are complex, difficult to spot, and often confused for other diseases. Studies suggest that over half (53%) of atypical young-onset Alzheimer’s cases receive an incorrect initial diagnosis. That’s more time bouncing from doctor to doctor until the individual receives the correct diagnosis and can begin treatment—but physicians and scientists are working to change it.

Learn more about the five types of Alzheimer’s disease that don’t start with your memory:

Types of Atypical Alzheimer’s Disease

Visuospatial

When your brain cannot process all the items that you see, it could be from progressive damage to your vision center, called posterior cortical atrophy (PCA). Also known as Benson syndrome, this atypical form of Alzheimer’s prevents someone from seeing everything in front of them. Finding keys on a cluttered table, solving a puzzle, driving, and other activities can become difficult. PCA is often mistaken for an eye condition rather than a brain disease. People with PCA may visit their eye doctor thinking that their glasses aren’t working anymore. An additional visit with a neurologist is needed to confirm a PCA diagnosis. This form of Alzheimer’s disease may disproportionately affect the occipital and parietal areas of the brain responsible for vision and processing sensory information.

Language

Primary progressive aphasia (PPA) is a condition caused by progressive damage to the brain’s speech and language hub in the temporal lobe. This damage causes increasing difficulty with communication, which can include speaking, reading, writing, and language comprehension. Like frontotemporal dementia, PPA appears as a primary symptom of the language form of atypical Alzheimer’s. Being at a loss for words, repeating sentences, and struggling with speech sounds, called logopenic PPA, is most commonly linked to atypical Alzheimer’s.

The similarity to frontotemporal dementia presents a challenge for healthcare providers, as frontotemporal dementia is the second most common dementia in young people. Physicians often must rely on brain scans to accurately distinguish between these two kinds of dementia. However, structural changes to the brain in each type may mimic each other. That’s where tools that specifically measure hallmark Alzheimer’s proteins can come into play, like specialized imaging or tests using cerebrospinal fluid or blood.

Executive

The front of the brain houses some of the most critical components of what makes you “you.” When Alzheimer’s attacks this area, called frontal-variant Alzheimer’s, it can affect your organizational thinking or your personality and behavior. Recent work highlights that brain areas associated with these functions, the frontal and parietal lobes, may be affected in the dysexecutive form of Alzheimer’s.

Those with the dysexecutive form of Alzheimer’s may struggle with playing board games, following directions, and organizing their calendar. Their ability to coordinate their actions and plan are hindered by the damage occurring in their brain. Dysexecutive Alzheimer’s is commonly confused with psychiatric conditions like anxiety and depression. However, this form of atypical Alzheimer’s rarely presents with behavioral and personality changes outside of apathy.

Behavioral

The second form of frontal-variant Alzheimer’s impacts behavior and is the least common type of atypical Alzheimer’s. Symptoms can appear as any action that is typically out of character for that person. Maybe a person begins eating off other’s plates when they never did before or suddenly gains an intense craving for sweets.

Now just because someone is going through a behavioral change doesn’t necessarily mean they have Alzheimer’s. Biological tests for Alzheimer’s like those mentioned above can help determine if there is something more to it. They can also help distinguish behavioral Alzheimer’s from the behavioral version of frontotemporal dementia.

Motor

The motor variant of atypical Alzheimer’s is unique in that those with this condition may show signs from the other types as well. A person can have behavioral changes, visual disturbances, impaired organizational thinking, or language difficulties, but the presence of motor challenges sets them apart.

Rigid limbs, slow or involuntary movements, difficulty performing physical tasks, sensory deficits, and even alien limb phenomenon are all symptoms of corticobasal syndrome. While typically due to a similarly named degenerative disorder, a portion of these cases are attributed to atypical Alzheimer’s. Many of these same symptoms are also present in Parkinson’s disease.

Risk Factors for Atypical Alzheimer’s Disease

Genetics

The strongest genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease is possession of the APOE e4 variant, but this risk gene is most associated with late-onset Alzheimer’s, the most common form of the disease. As much of our understanding of Alzheimer’s is from older people, this initially impacted our genetic understanding as well. Now, research is beginning to show that APOE e4 may not be as big of a contributor for non-memory atypical forms of the disease. Additional studies are underway to identify other genetic variants that may be more associated with atypical Alzheimer’s.

Sex Differences

Alzheimer’s typically impacts more women than men—but atypical Alzheimer’s may be an exception. While visuospatial and motor variants still impact more women, the behavioral type appears to be more common in men. Dysexecutive and language forms of atypical Alzheimer’s appears to be more evenly split between the sexes. Researchers are still investigating the underlying biological reasons for these sex differences.

Summary

Every person living with Alzheimer’s deserves effective treatment. We are shining a light on the less common forms of this disease to raise awareness and continue advancing better care for Alzheimer’s. Young people with dementia need their caregivers and healthcare providers to see the signs and help affected individuals navigate the journey to accurate diagnosis and treatment.

Atypical Alzheimer’s fundamentally challenges our understanding of this disease. It occurs at an earlier age, damages different brain areas, and does not begin with memory loss. But there’s hope—the modern era of biomarkers has provided a huge amount of insight into people living with atypical Alzheimer’s. With continued scientific investment and collaboration, we can create a better path forward for the individuals, caregivers, and families affected by this disease.

BrightFocus Foundation is committed to empowering precision tools for earlier and more accurate detection and diagnosis of Alzheimer’s. Check out Alzheimer’s Disease Research grant recipients who are advancing early detection and improved diagnostics here.

About BrightFocus Foundation

BrightFocus Foundation is a premier global nonprofit funder of research to defeat Alzheimer’s, macular degeneration, and glaucoma. Since its inception more than 50 years ago, BrightFocus and its flagship research programs—Alzheimer’s Disease Research, Macular Degeneration Research, and National Glaucoma Research—has awarded more than $300 million in research grants to scientists around the world, catalyzing thousands of scientific breakthroughs, life-enhancing treatments, and diagnostic tools. We also share the latest research findings, expert information, and resources to empower the millions impacted by these devastating diseases. Learn more at brightfocus.org.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is a public service of BrightFocus Foundation and is not intended to constitute medical advice. Please consult your physician for personalized medical, dietary, and/or exercise advice. Any medications or supplements should only be taken under medical supervision. BrightFocus Foundation does not endorse any medical products or therapies.

- Brain Health

- Other Dementias

- Risk Factors