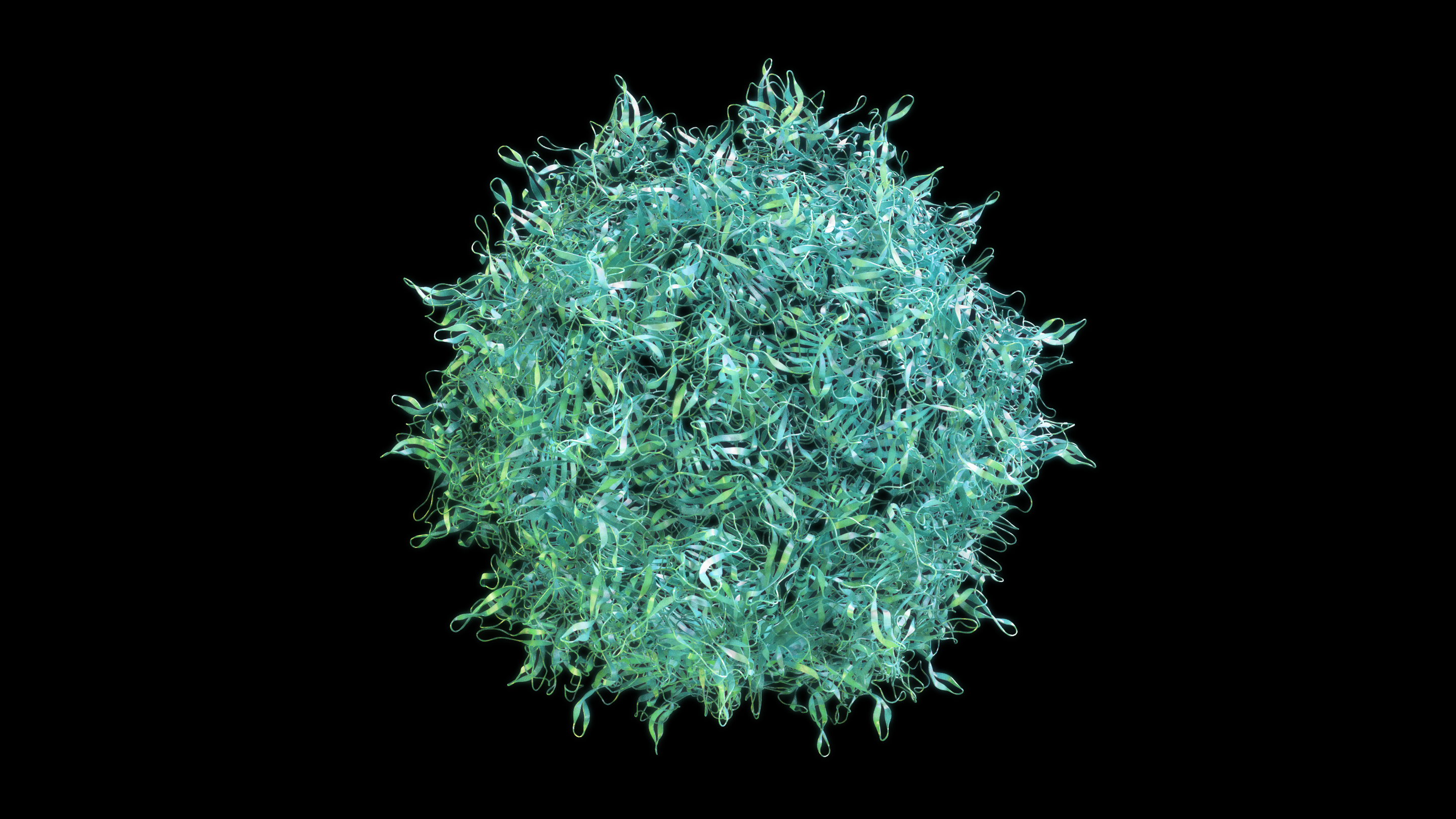

A digital rendering of an adeno-associated virus (AAV), commonly used in optogenetics research.

Key Takeaways

- Optogenetics is an emerging approach that combines gene therapy and light to restore some visual function in retinal diseases.

- It works by making surviving retinal cells light-sensitive, offering hope even in advanced macular degeneration.

- Early clinical trials have shown safety and signs of effectiveness, with more therapies in development.

Therapies based on a new technology that combines gene therapy and light, called optogenetics, are showing success for restoring partial vision in people with inherited retinal diseases. When retinal cells responsible for sensing light have been disabled or destroyed, optogenetics can recreate this function in other cells.

Several optogenetic therapies are being studied as potential treatments for retinal diseases like age-related macular degeneration (AMD). “These tools have shown early efficacy (effectiveness) and safety,” said Dr. Cynthia X Qian, MD, a pediatric retinal surgeon and associate professor of ophthalmology at the University of Montreal in Quebec, Canada.

Most of this work has been done in inherited conditions such as retinitis pigmentosa and Stargardt disease, a form of juvenile macular degeneration.

However, “these strategies could be adapted for advanced AMD, especially geographic atrophy, where photoreceptor loss is a key issue,” Dr. Qian noted. A new tool for treating this form of dry AMD is particularly exciting, she added, since current treatments can only slow progression of the disease, and don’t improve vision.

How Optogenetic Therapies Work

In many eye diseases, vision loss occurs when light-sensitive photoreceptor cells in the retina stop working or die off completely. Photoreceptors are the only retinal cells that produce opsins, proteins that give photoreceptors their light-sensing ability. Opsins act like a sort of switch. When exposed to light, they trigger an electrical signal that travels to the brain.

Optogenetics can turn other, surviving types of retinal cells into a backup system for faulty and dead photoreceptors. Here’s how the most common method works. A harmless virus is loaded with a gene that contains instructions for making an opsin. The virus is altered to target a certain type of retinal cell—such as a ganglion cell—that remains intact in a particular disease.

When injected into the eye, the virus delivers the gene to the target cells, which ‘take up’ the gene. The cells can then begin making opsin. When exposed to light, these proteins set off an electrical signal. This can “restore some visual responses in a blind retina,” explained Dr. José-Alain Sahel, professor of ophthalmology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. An international expert in treating retinal diseases, Dr. Sahel was involved in the first reported case of successfully using optogenetics to restore partial vision.

Limits and Advantages

It’s important to understand that optogenetics does not restore normal vision. Instead, “it has the potential to restore some central vision performance,” said Dr. Sahel. This partial, artificial vision is something like the hearing that some deaf people gain after receiving a cochlear implant. And some optogenetic therapies must be used in conjunction with special devices, such as light-amplifying goggles, as well. The resulting vision can give people back abilities such as locating objects on a table and detecting movement.

Several factors make optogenetics especially promising for treating retinal disease. For one, it doesn’t just act on a single gene or gene mutation, meaning it could be used in many different diseases. It could also be a one-and-done treatment, since it genetically alters cells to continue producing opsin. Optogenetics can also activate multiple cells and is less invasive than surgery to implant cells or a device into the retina, according to Dr. Sahel.

In AMD, optogenetic-based therapies would offer another advantage: they could be used even in late-stage disease, when no working photoreceptors are left.

Applying Optogenetics to Age-Related Macular Degeneration

Several optogenetic therapies are currently in the research pipeline for AMD.

Ray Therapeutics is developing an optogenetics platform called RTX-021 for geographic atrophy. Still in the pre-clinical stage (which means it hasn’t yet been tested in humans), RTX-021 targets bipolar cells in the retina. This therapy doesn’t use any external device.

MCO-010, from Nanoscope Therapeutics, also acts on bipolar cells, and doesn’t involve special eyewear. The therapy will reach Phase 3 clinical trials in retinitis pigmentosa and Stargardt disease in late 2025. It will soon be tested in Phase 2 clinical trials for geographic atrophy.

Three other companies have also been testing treatments for retinitis pigmentosa with an eye to applying them to AMD in future. All three therapies use optogenetics to target retinal ganglion cells in combination with a device.

In the case of Science Eye, an implant is surgically placed in the retina. G030, from GenSight Biologics, stimulates the treated retina with goggles that look like the ones from virtual reality games. The device component of Bionic Sight’s BS01 platform is also external, worn like a pair of glasses.

“Optogenetics is no longer just theoretical—it is in human clinical trials, with real evidence of visual function restoration,” said Dr. Qian. “Continued funding is essential to refine these tools further and expand them to more prevalent conditions like AMD.”

Summary

In diseases like AMD, vision loss can happen when light-sensitive photoreceptor cells in the retina stop working or die off completely. Optogenetic therapies can create a back-up system for the lost photoreceptors. Introducing a gene into a different type of retinal cell that isn’t affected by the disease allows these cells to make light-sensitive protein. This approach can restore some functional vision.

“Optogenetics is one of the most promising vision restoration strategies,” said Dr. Sahel. “It is a breakthrough technology and multiple very promising developments are underway.”