Alzheimer's Clinical Trials 2024: The Inside Story with Dr. Jeffrey Cummings

Zoom In on Dementia & Alzheimer's

Featuring

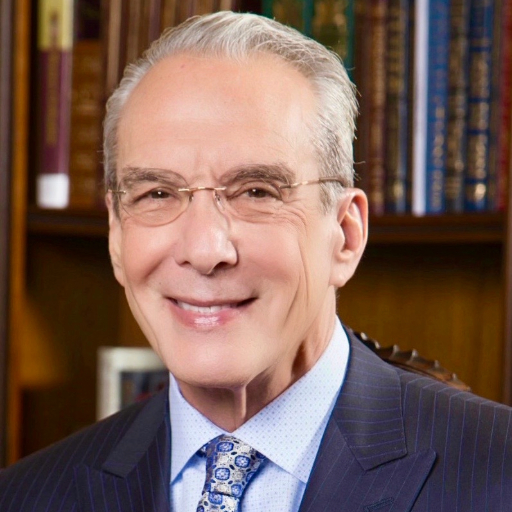

Jeffrey Cummings, MD, ScD

Professor of Brain Science University of Nevada Las Vegas

Zoom In on Dementia & Alzheimer's

Jeffrey Cummings, MD, ScD

Professor of Brain Science University of Nevada Las Vegas

In 2023, there were 184 trials assessing 143 drugs for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Mild Cognitive Impairment, with more than 60,000 participants required to populate those registered trials at 5684 sites. What is happening in 2024? Listen to Dr. Jeffrey Cummings for the insider’s overview.

NANCY LYNN: Good morning, good evening. We’re delighted to welcome everyone to Zoom in on Dementia & Alzheimer’s, a free monthly program that is supported in part by educational grants from Lilly and Genentech. I’m Nancy Lynn from BrightFocus Foundation, an organization that has funded nearly $300 million in research globally for Alzheimer’s disease, macular degeneration, and glaucoma. And also on with us today from BrightFocus Foundation is Dr. Sharyn Rossi, who manages our Alzheimer’s portfolio. She will help answer questions as you put them in the chat while our guest expert is speaking. I just want to mention that we had over 500 registrants and over 110 questions pre submitted. And they were fantastic questions but some of them were on the topic of clinical trials, and many were not. So if your question isn’t answered today, I want to refer you to the programs we’ve already done, which you can download on our website. You can just go and click on them in here. A lot of them are about the new drugs: “What is Leqembi?”, “New Alzheimer’s Drugs: What To Expect Over The Next 3 Years.” All of them presented by some of the greatest minds in Alzheimer’s today. Also we have a lot of questions on genetics and is Alzheimer’s hereditary? We do have an episode online with Dr. John Hardy that you can refer to. “How Is Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosed?” with Dr. Randy Bateman. So these are all available to you and next month we’re going to be doing an episode about what are the stages of Alzheimer’s disease and we’ve also been asked to do an episode on non-drug intervention. So those are all coming up and I encourage everyone to keep asking us, sending us questions because we really have a great idea of what everybody wants desperately to know.

So I’m going to jump in and introduce Dr. Jeff Cummings. Dr. Jeffrey Cummings is Joy Chambers-Grundy Professor of Brain Science, Director of the Chambers-Gundy Center for Transformative Neuroscience, and Co-Director of the Pam Quirk Brain Health and Biomarker Laboratory, Department of Brain Health, University of Nevada Las Vegas. I hope I got that right Jeff. He is globally known for his contributions to Alzheimer’s research, drug development, and clinical trials. And also, for contributions to the field by his wonderful wife, my friend, Dr. Kate Zhong. Dr. Cummings was formerly Director of Mary S. Easton Center for Alzheimer’s Disease Research at UCLA, and Director of Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health. He’s in Las Vegas. He’s going to be playing in the Super Bowl this year. Welcome, Dr. Cummings.

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Thank you very much, Nancy. Really great to be here.

NANCY LYNN: And this is a slide that Dr. Cummings presents at scientific conferences all over the world. It’s really quite incredible and we showed it on one of our episodes briefly. I call it the clinical trials circle, a chart showing all of the clinical trials that were for Alzheimer’s disease related therapeutics that were happening in 2023. And I’ve heard him at many scientific conferences you’ll see here talking about big small molecules, biologics. This is my mom. Her name is Judy. She’s going to turn 94 next month and she’s watching this in the living room in West Virginia, hello, with her friend Madeline who’s in her seventies and my sister who’s in her sixties. So today I’m going to ask you to look at the chart, and talk to this audience and my mom and Maddie and Robin about what does this mean to those of us who are not scientists? What can we learn from this and what would you like to tell us about this?

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Absolutely. Thank you, Nancy. Really great to be here. I looked over some of the questions that came in and I could see that many of you are living with Alzheimer’s, living with someone who has Alzheimer’s, have those immediate and urgent questions that affect your life every day. So I’ll answer those as Nancy asks them, but I did think it would be useful to look at the clinical trials landscape before we plunge into that. This is an annual publication that we do in Alzheimer’s and dementia. This is our eighth year of publication of this so we have been at it a long time with a very large database of drugs that have been in trials or are currently in trials. So first I’ll take you through the figure itself and then I’ll tell you a little bit about the changes that we’re seeing in the pipeline as we’re looking at it this month because we look in January to understand what’s happening in clinical trials. And then we publish it following that. So I am every day studying the clinical trials that are currently going on.

So let’s look at the circle on the left. And you see there’s an outer circle, and that’s it has only a few dots in it, and that’s the Phase 1. So Phase 1 starts with healthy volunteers. First, you test a drug in animals. Everything looks like it’s affecting Alzheimer’s disease, and you would begin testing it in healthy volunteers. And that way you begin to understand how the drug is handled by the human body. If that looks good. Go into Phase 2 and that now is usually the first exposure for patients with Alzheimer’s. So that’s the middle circle of the circle on the left. If that goes well, then it would be advanced to Phase 3, and that is the internal, the smallest circle in the circle on the left. And if that went well, then the drug would be presented to the FDA and for possible approval. And you know that we have had two approvals lately, one for aducanumab or Aduhelm and one for lecanemab or Leqembi. And we’re expecting an approval, although we don’t know for sure, of donanemab in the first quarter of this year. So some drugs are going on.

It’s notable that there’s about a 99% fail rate for drug development for Alzheimer’s disease. So most of these molecules that you see here represented by a colored dot will not go on to be presented to the FDA. But you have to test a lot of drugs in order to get a few drugs that succeed. And I think we are getting better and better at identifying the drugs that are likely to succeed, and therefore I think the failure rate will go down. That we’ll see more and more success over time.

So, now I’m going to talk a little bit to the table on the right here. So the figure I’m showing you is our 2023 figure. And then we’re just as I say this month looking at 2024. The first thing that jumped out at us is that there are fewer trials and fewer drugs this year compared to last year. So that you see that in 2023 there were 187 trials. In 2024 there are 171. You see that in 2023 there were 141 drugs in trials. That’s because some drugs are in more than one trial. That’s why there are more trials than drugs. And this year there are 134 drugs in trials. So this is of course a trend that we do not like to see. We want more and more interest in Alzheimer’s disease, more and more drugs, more and more trials. That’s how we get to effective therapies that you and your loved ones need.

Now let’s look at the composition. I’m using the initials DMT. That stands for disease modifying therapy. The point of a DMT is to interfere in the biology of Alzheimer’s disease to slow the progression of the disease. Patients do not get better. They lose their skills less rapidly. That’s very important. And you see that roughly 78 or 77%, it’s almost the same both years, of drugs in the pipeline are devoted to this idea. Can we slow the disease? And eventually of course if we could slow it completely, we could arrest the disease. But we start by slowing the disease. Right now the drugs that have been approved slow the disease by about 30%. So patients who are in the mild phase of the disease for 3 years, on treatment, would be in the mild phase of the disease for about 4 years. That’s a meaningful difference from most of our point of view.

Now below that you see DMT biologics. Now these are drugs that are administered intravenously, usually. Although they can be administered subcutaneously, or they can be injected directly into the spinal fluid that surrounds the brain. So, and again you see the percentage of biologics is almost the same both years. And these are the drugs that are succeeding now. The drugs that are approved or are likely to be approved are administered intravenously, because they are not absorbed if you give them by mouth.

The ones that are absorbed are that next slide category, DMT small molecule. A small molecule is usually given by mouth. And of course, that’s what we want, right? Much easier to give a drug by mouth than it is intravenously. So we’re trying to develop drugs. And you see there’s a lot of work there. It’s actually the largest area in the pipeline are the disease modifying small molecules.

Then there’s a little work on cognitive enhancers. These are drugs that make people better. They improve memory. In general, they do not slow the disease. They simply improve it. The person continues to deteriorate, but they have this this improvement. And that’s what the current drugs like the Donepezil and Rivastigmine and Galantamine and Memantine all do. They’re all cognitive enhancers. They improve people’s memory temporarily. They do not slow decline. We’re really happy to have them. Had them for 20 years. But they’re not enough. And so it’s a combination of cognitive enhancer and disease slowing that we’re trying to move towards. But there are a few cognitive behaviors, 11% of the pipeline.

Drugs for neuropsychiatric symptoms are also very important. And I saw this in the list of questions that had come in. People were asking about sundowning, which is agitation that occurs in the evening. And then there’s agitation that occurs more or less all the time: there’s psychosis, there’s depression, there’s apathy or sleep disturbances, all common in Alzheimer’s disease. And about 11% of the pipeline is devoted to these drugs that help neuropsychiatric symptoms. And again, we’ve had our first approval in 2023 of a drug for agitation in Alzheimer’s disease called brexpiprazole. And that for me is very important because it opens the pathway for drugs for psychosis, drugs for sleep disturbances, drugs for apathy. We’re starting to know how to develop these drugs for the behavioral changes that are so disabling for the patient and the carer of patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

Then the last point I’ll make about this slide and then we can go on to the questions is repurposed drugs. Now, a repurposed drug is a drug that’s approved for some other non-Alzheimer’s indication but there’s something about the biology of that drug that suggests that it might be worthwhile to test in Alzheimer’s disease. A big advantage of these drugs is that they’re often cheap because they’re often old enough to be off patent. So they can be tested with a smaller budget. We also know a lot about the safety of these drugs. Because they’ve been tested for these other indications. So there are a couple of good reasons to test repurpose drugs, and you’ll see that they are actually occupying a larger segment of the pipeline this year than last year. They’ve increased from 28% to 40% of the pipeline. So we’re seeing more and more repurposed compounds coming into the pipeline. So Nancy, I think maybe that’s enough about the pipeline unless you would like me to clarify something? And we could go on to the questions or you tell me what’s next.

NANCY LYNN: Sure, I’m very interested and happy to hear you talk about dementia related apathy and the real sort of, real world effects of having the disease. And in the field we talk about it as activities of daily living. How long can you actually function independently and interact with people in a way where you’re more independent than less? And I think someone was writing questions in the chat box about slowing down: what does slowing mean? What does, you know, how effective is effective? That kind of question with the current drugs on the market. And so I would say to you just to real quickly address: What does it mean that Leqembi and Donanemab, if it’s approved, Aduhelm, when we talk about how these therapeutics or lifestyle interventions will affect people, what are we looking for when we say slow it down?

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Yes, I think slowing is a difficult concept. When we think about treatment, we think about getting better. But in with these drugs one doesn’t get better. One loses abilities more slowly. And we talk about that in terms of time saved. I want my time saved that I can still drive. I want my time saved that I can still take care of myself. I want my time saved that I can enjoy my interactions with my friends. So I think the idea of time saved is a good way to think about slowing of disease. Slowing is the measurement that we make in a clinical trial. What does that mean to the person? To the person it means time saved in terms of their ability to do things that they value.

One of the very interesting observations of the of the data that we’ve seen in a very small number of trials that have been performed so far on these advanced drugs is that the effect on function, what Nancy is calling activities of daily living, your ability to actually dress herself and take care of yourself and find your way and all of that, the effect is actually somewhat larger on those measures then they are on the cognitive measures where we see a smaller effect. So we’re getting a larger effect from these drugs on function and a somewhat smaller effect on things like the actual memory that the person has. They must succeed on memory in order to be approved and they have. But it’s very interesting to see that we’re also having a benefit on function and if anything it’s a larger benefit.

NANCY LYNN: Thank you. And Jody in the chat is asking a question that a lot of people asked in advance: Are there studies focusing on prevention? And she specifically says for those with higher risk due to family history and genetic indicators, such as APOE4. And so we did get several questions about APOE4 and other types of people call it prevention and I like to say risk reduction because I don’t know if there’s anything that is currently in the pipeline that we think can prevent the disease. But just like with smoking, you can’t prevent cancer, but you can reduce your risk by not smoking. Why don’t you speak to trials that deal with risk reduction or are preclinical.

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Yes. So really great question, Jody. Thank you for asking this. They are called prevention trials. And Nancy is absolutely right. We’re not sure that for any single individual we can prevent Alzheimer’s disease. What we what we are trying to do is to delay the onset of the cognitive loss. And we currently have 2 advanced trials in people who were cognitively normal when they started the trial but they had levels of protein in the brain that suggested that they already had Alzheimer’s starting in the brain. So we can measure that with a scan. So there’s a trial of lecanemab or Leqembi and there’s a trial of the donanemab in people who are cognitively normal. Those trials have, the recruitment has been completed and now we’re just watching to see until the trial actually ends, which is when you determine whether it had the effect of slowing the onset of the cognitive decline. So those are very important trials. That’s called secondary prevention because the protein that causes Alzheimer’s is already in the brain. Now it’s a very exciting scientific idea and could be a very important public health idea if we could do primary prevention. Which is to understand who’s likely to get Alzheimer’s disease, but is still has no protein in the brain and can we reduce the likelihood of getting the protein? And so those studies, there are none of those currently going. But they are being considered and I think we will see them. So there will be trials of primary prevention where people have no protein in the brain and are normal, of course. And there are trials of secondary prevention where people are cognitively normal but do have the protein in the brain. They just haven’t triggered enough of the process of Alzheimer’s disease to have the memory impairment. The question there is, can we delay the memory impairment? So those trials are ongoing, we’re going to have some answers by, these are long trials, takes a long time to determine, but by 2027 we will have answers to those trials.

NANCY LYNN: So if I understand you, you said that there are no trials currently running for Leqembi or donanemab or aducanumab, in the secondary prevention space but what about trials that test things like sleep, or reduction in diet, exercise, or other types of non-pharmaceutical, sorry to use the jargon, but they call them interventions. Are there some trials that you think are quite worthy that people could participate in today?

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Yes, thank you. And let me be clear, there are 2 secondary prevention trials ongoing. One with donanemab and one with lecanemab.

NANCY LYNN: What are those trials called?

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: The lecanemab trial is called AHEAD. And the donanemab trial is called TRAILBLAZER-3. So you ask about the non-pharmacologic trials, and this is not my area, but it is an area of great excitement. And it is the biggest hope for the world in terms of prevention of Alzheimer’s disease or risk reduction in terms of the point you made. So we know that exercise and diet both have a very important effect on the risk for Alzheimer’s disease. And we have pretty good data that if somebody has mild impairment, diet and exercise and taking care of the cardiac and stroke risk factors can also help slow the loss of function during that period. And there is a trial going on called FINGERS. I think in the United States it might be called POINTER. And this is sponsored with the Alzheimer’s Association and led by an investigator called Miia Kivipelto. And Miia did a FINGER study in Finland, that’s where FIN comes from in FINGERS, and showed that it slowed the progression of cognitive loss in people who had mild loss. And so that trial is now being redone on a worldwide basis. So there’s a whole network of sites worldwide doing worldwide FINGERS. And Miia is a very creative investigator and she just started a combination trial of a drug, metformin, used in diabetes and seems to have an effect on Alzheimer’s with exercise. Because what do we want? Well, we want to get all of the arrows in our quiver shot in a way that makes it most likely that we can help patients and their caregivers. So let’s try some of these things together and we’re thinking more and more about what combinations make sense. I just came from a meeting in New York this week where we thought about this all day. What combinations make sense? And I think we’ll see more and more combination trials coming out.

NANCY LYNN: Just looking through. Yeah, FINGERS and POINTERS study and we actually have asked Dr. Kivipelto to come on in the future to talk about the work that she’s doing.

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: She’s great.

NANCY LYNN: She’s wonderful. I’m going to get to the questions that are coming into the chat box, but the first one was, “Is there anything happening in the moderate stage?” And we received several questions about is there anything in middle stage, late stage and one person asked who participated in the AHEAD study for 6 or 7 years and then had to stop, was interested in what else they could do. So are there options for people who are a little more advanced or much more advanced?

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Yes. Again, really great question. The antibodies Leqembi and donanemab that we’ve been talking about are limited to patients who have mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease or very mild dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease. So it’s a small window of the entire spectrum of Alzheimer’s disease. Most, well, many of the small molecules that are being tested and we talked about the difference between biologics which is like Leqembi and donanemab and small molecules that you can take by mouth. Many of those trials are being tested in mild and moderate Alzheimer’s disease and a few include patients with severe Alzheimer’s disease. So yes, there are trials for mild, moderate, and severe Alzheimer’s disease. I was just contacted this morning by a company that has a drug that they think would help people with severe Alzheimer’s disease. It’ll be a, you know, a year before that drug goes into trials, but there is interest and we know that we have to help more patients, right. The idea that we’re only going to help patients who have mild disease. That’s an unacceptable idea. So, we will be doing more and more trials, I think, with mild to moderate disease. It makes sense, of course, that the less affected the brain is the more likely it is to respond to therapy, right. That makes sense. And so there’s a great motivation to test drugs when patients are very mildly affected because that’s where the drug is most likely to succeed. But there’s every reason to believe that some of these drugs that affect tau, for example, or inflammation in the brain, may well help patients in more severe aspects of the disease and they are being tested in those patients.

NANCY LYNN: Since you just mentioned it, I’ll ask you briefly because somebody asked the question, what do you think is the most exciting tau related trial being done?

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Yeah, well the most exciting tau drug right now is a drug from Biogen. And, I don’t think it has a name yet, 080 is its number. And it is a complicated drug. The patient gets a lumbar puncture and then the drug is introduced into the spinal fluid through the lumbar puncture. That lumber puncture only has to be done every 3 or 6 months. They’re currently determining which it is. And it had a dramatic effect on slowing the production of tau in the brain. A remarkable effect. And I’m really enthusiastic that that may be an effective drug and it may be effective for a wider range of patients than the current anti-amyloid drugs are. So, I’m really excited about that compound. There are other interesting tau drugs as well. But, that when you say, what’s the most exciting one? The most exciting one is this drug that interferes with the production of tau in the brain.

NANCY LYNN: Yeah, I know that was asked by a scientist sneaking their question in. You’ve mentioned a couple of studies now that are not available now but are available in the future. And I am going to get to the questions in the chat, but how do people find these trials? And if somebody, if you said something today that somebody is very eager to participate in a year from now, it’s hard for people, I think we wrote about 60,000 or so people are going to be needed for trials in 2024 and it’s so hard to find a trial that fits you and is near you. And BrightFocus has on our website a link you can go to on brightfocus.org/clinicaltrials. That is one of the easier to navigate widgets, we’d call it. So if you’re interested in finding a trial there, but a lot of those sites are hard to navigate. You, I think you guys have a site. Would you like to tell people about your site as well?

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Yes, thank you Nancy. Go to the BrightFocus site. You know that they’ll have a real hands-on approach and will help you.

NANCY LYNN: And also if you really, really want to participate in a trial and find something near you and you haven’t been able, you can email me, you can email us at BrightFocus and we will try to help you, you know, through our network of research scientists find what fits you nearby. We will offer that to you on a personal basis. We can’t recommend or advocate for any particular trials, but we can just help you navigate there.

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: That’s great. And trials are difficult. First of all, I’ll tell you about our site, which is AlzPipeline.com. If you go to the Insights section, there’s a map. And if you can find a dot close to where you live, click on the dot, and it’ll tell you about the trial. But they’re complicated and it’s complicated to use these various tools. And I encourage you to use the BrightFocus hands-on help that they can provide. But you can get some idea from looking at our map on the AlzPipeline.com website. We hope to improve that over time.

I want to say something about eligibility for clinical trials. When you’re doing a clinical trial, you’re trying to find out does the drug work? And therefore, you want a pretty well-defined population. So people have to be of a certain age. They cannot be on some medications. They cannot have some past history of certain disorders. And the eligibility criteria are pretty severe. Because you want to test the drug on people who have pretty pure Alzheimer’s disease. Even when we try to do that, we know there’s a lot of heterogeneity. So we want to try to test it as purely as we can so we can see if the drug works. And then later, the drug can be generalized to a wider population. But you say you want to be in a clinical trial and you can’t find one that will accept you. That’s why. That is because there are many eligibility criteria for trials. And it’s a great paradox for us as scientists who do trials. Because we want to know does the drug work broadly. But first we have to know does a drug work narrowly? And so it’s a process.

NANCY LYNN: And there’s a bunch of questions coming in. This may need another episode and we sure hope you’ll come back. But people are asking about trials for non-Alzheimer’s dementias. So we know that dementia is an umbrella term about a condition starts broadly and we’ve gone over this. And then there’s dementia caused by Alzheimer’s disease. And people, I apologize for not asking all of the specific questions because they have been specific questions about specific non-Alzheimer’s dementias, but generally speaking are there trials for those and also how are they distinguished? A lot of people are asking how are they distinguished.

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Yes. So there are trials for non-Alzheimer’s dementia and when we say non-Alzheimer’s dementia we’re basically talking about frontotemporal dementia, this is the Bruce Willis disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, so that’s another relatively common disorder, and vascular dementia, which is a relatively common disorder. And there are trials for these disorders, but they’re much more unusual or uncommon than trials for Alzheimer’s disease. Why is that? Well, it’s because there are millions of Alzheimer’s patients and there are maybe a few 100,000 maybe even less of the more rare dementias. So companies and academics start with the big population so that you can understand what the drug is doing in Alzheimer’s. And then you might take that next step if it looks successful to another set of disorders. Now here’s the exciting part. From my point of view is that what we’re learning in Alzheimer’s disease looks like it’s going to help us with other disorders. For example, we just talked about this tau drug. Well, there are tauopathies and the tau causes frontotemporal dementia. So if we understand how to control tau in Alzheimer’s disease, it’s an easy step to think about how to control tau in frontotemporal dementia.

Similarly, we know that Alzheimer’s disease is causing inflammation in the brain. And that inflammation makes the dementia worse. But so does every other dementia. So if we could control the inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease, we could take that lesson and use it in other dementias. So I am excited about the exportability of the of our learnings in Alzheimer’s to other dementias. We have to do that! This is ridiculous that we don’t have more trials in these other disorders. And I will say that the government, the NINDS for example, most of the non-Alzheimer’s dementias are funded, they are very interested in finding trial with these drugs.

NANCY LYNN: Yeah, and I know somebody asked twice and so I think she really wants to know about late dementia, and TDP-43, and I’ll just mention it because I guess there are no identifiable biomarkers right now that we can find in people while they’re alive. Do you see any hope on the horizon there for finding biomarkers for late?

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Yes, so TDP-43 is a protein sort of like the protein of amyloid and the protein of tau and it’s also present in Alzheimer’s disease. It accounts for half of all of the cases of frontotemporal dementia. It accounts for almost all of the cases of ALS. So this is a common protein. It’s a toxic protein. We have no biomarker for TDP-43 itself. We desperately need it and scientists are out there looking for that right now. And I have seen some preliminary presentations. None of them are completely cooked yet in a way that could get into clinical practice or even into clinical trials. But it is an obvious sort of gap in our understanding and our availability of biomarkers. So I’m sure that there’s going to be progress there. I’m sure that that’s going to open the door to the TDP-43 part of Alzheimer’s disease but also to these other TDP-43 drugs. There have been a couple of drugs now approved for ALS. And they have to be working through, at least partially through, these TDP-43 effects. Or at least some of them do. One of them is very specific for hereditary disease and that might not be TDP-43. But the more general drugs that have been approved might be working through TDP-43. So again, just as we think we can export learnings from Alzheimer’s to other dementia, we also think we can import learnings from other dementia into Alzheimer’s disease. And ALS is one of the most active areas right now. So, I certainly follow that, try to understand, and see if there’s anything we can do with that information for Alzheimer’s patients.

NANCY LYNN: Well, I’m going to call on Michael now, and, but I promise everybody because we’ve received so many questions about the 60 Minutes episode on ultrasound. So I promise everybody after Michael’s question that we will ask Dr. Cummings about that. Go ahead, Michael.

MICHAEL: Good to see you, Dr. Cummings. I’ll tell you, we’re living in exciting times and I’m just wondering what your thoughts are. As you know, the brain barriers been a big problem getting the drugs through the brain barrier. However, it looks like we’ve now done three good studies that have proven using ultrasound, was allowing the drugs to be very effective. Do you see that changing? The whole spectrum of how we start to use drugs now because of this? You know, we’ve had many get failed because of that. What’s your thoughts on this?

NANCY LYNN: Thanks for teeing that up, Michael.

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Thank you, Michael. Really great question. And, so yes, that ultrasound work is really interesting. And I saw it presented earlier in the year and then of course it was published just what two weeks ago in the New England Journal and it shows that when you give the antibody, the biologic aducanumab, and then give ultrasound in an area of the brain, you get more of the aducanumab, and more of the removal of the toxic protein in the area where the ultrasound interrupted the blood-brain barrier. So that looks very promising. Here’s one worry that has to be resolved. The blood-brain barrier protects your brain from infection. So we’ll have to know for sure that interrupting the blood-brain barrier does not somehow predispose the patient to getting infections in the brain that would normally be excluded by the blood-brain barrier. So we will have to learn that. It’s been only a small number of patients as you know that have had this ultrasound treatment. Not enough to know its safety yet. But the promise looks great. And the idea of getting drugs across the blood-brain barrier is a central problem in therapeutics for all CNS diseases and particularly for all Alzheimer’s.

There is one company, Roche, that’s working with their antibody and attaching it to a natural transporter across the blood-brain barrier. So that that transporter then can transport the molecule, the treatment, across the blood-brain barrier. And in that case, the blood-brain barrier stays intact because it’s using a natural transport mechanism. So they’re a variety of ways to see, well, can we defeat the negative aspects of the blood-brain barrier? Particularly well preserving the positive aspects of the blood-brain barrier. So it’s a really exciting set of ideas and I’m just delighted actually to see this going on. Really important work.

NANCY LYNN: And how nice that 60 Minutes amplified it so much. You talked a little bit before about entry criteria. That if you have diabetes or high blood pressure or a lot of other conditions it can be very hard to get into a trial. We have a lot of questions about ways that people can participate if they don’t meet the eligibility standards. And I think this is really important. I want to ask you to talk a little bit about maybe decentralized trials, but I just want to read this one question that came in out of the 100 over a hundred that touched me. It’s from Richard in Vero Beach and he said, “I feel I’m on the border. I’m 78 and suffer from PTSD from combat in Vietnam. I’ve been tested for and determined that I have mild cognitive disorder. I have a BS in engineering and an MS in math. I was told the many things I used to do, I no longer can do. With 3 shoot downs in 1969-70.” And he had double knee replacement so he’s not mobile and I know there’s a lot of people who don’t have transportation and so on. He said, “I can’t do anything. I have a walker and cane, very frustrating. I’m looking forward to this seminar.” So for people who can’t get out and go through all the rigor of finding a trial and participating in a trial or don’t have a care partner which is often required, what do you recommend for them to do? For these wonderful heroic people who still want to participate in research somehow.

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Yes, well, thank you for all of the things that you’ve done in your life to help us. Now we would like to help you, of course. The things that are within reach for everyone are more exercise, and I realize you’re with a walker and you’re not able to walk. As a person, by the way, who’s had a knee replacement, I encourage you to do all of the exercises required and work on those stairs. Those are among the hardest things, but they are also among the things that can get you closer to normal walking. So please do those things. Do as much exercise as you can, even though you’re in a walker. You have upper extremity abilities. Yes, you are at increased risk because of your PTSD for mild cognitive impairment and for dementia. We know that Alzheimer’s disease is a combination of the disease process and the resistance of the host, and we are the potential hosts. So people who have a lot of resistance can have quite a lot of Alzheimer’s in the brain before they get many symptoms. People who have lower resistance, and PTSD lowers your resistance, will get Alzheimer’s disease with less of a disease burden, get the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. It’s very important to do everything you can. And lifestyle changes: your diet, how much you drink, whether you smoke, controlling your blood pressure. All of those things can help you increase your resilience to the disease. So they’re very important to do, so please do as much of it as you can even though you have substantial limitations.

NANCY LYNN: And if Richard has mild cognitive impairment and if he’s not mobile, is he potentially eligible for Leqembi infusion or any of the therapeutics that are on the market if somehow, they could be brought to him or he could get to them?

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Absolutely. It’s mild cognitive impairment for which these drugs are approved. And you know, a doctor would, or a clinician would need to review his medical history and review the criteria even though it’s no longer a trial, it’s an approved medication. There are still good reasons to try to avoid exposing people who might be at very high risk for the complications of these drugs. And these drugs do have complications, important complications. And so it’s a matter of getting to a medical facility that is providing Leqembi and will be providing donanemab soon, assuming that it’s approved.

NANCY LYNN: Three donors have asked us about using ketones. Now, I don’t know what that is. Do you? Can you comment on that?

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Yes, there’s been a lot of interest in ketones. The brain normally uses glucose or blood sugar for its metabolism but that process is compromised in Alzheimer’s disease. And an alternate energy source for cells of the brain are called ketones. There’s been a lot of interest in knowing whether we can increase the ketones in the brain. And therefore, improve its function at a time when it can’t use glucose. And there is preliminary support of information. This might be part of the coconut milk story. Although I’m not encouraging it because you don’t know how much to use for how long. There was a drug on the market for a while called Axona, that increases ketones in the brain. There was a very interesting data set with that. And that company is now advancing that idea, even though Axona is no longer on the market. Better formulations of Axona have been developed and are being tested now. So the idea of ketones, really important and I don’t think there is a ketone drug in the pipeline right now. No, no, that’s right. The Axona follow on is in the pipeline right now. So there’s a little activity even right now on ketones. I don’t know that they are recruiting right now. You know, there’s a period of recruitment in the trial. And then there’s a period where the patient gets the drug, but recruitment has stopped. So a drug can be in the pipeline without there being any recruitment going on at that time.

NANCY LYNN: Well, as Michael said earlier, these are very exciting times and we have discussed in prior episodes about new blood tests for Alzheimer’s. And I think related to the topic today, if you could talk a little bit about the new blood tests and how will they affect, do you think, the future, the present and future of participation in research and participation in studies?

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Yes, this is so exciting because I think it really has the opportunity to be a game changer. Let me say, before I start, some comments that I’m the chair of the Scientific Advisory Board for ALZpath and ALZpath is the company that has the drug that has been in thenews, not the drug, the blood test that has been in the news this week. So I’m not going to promote it specifically. I’m going to talk about blood tests in general, but I do want to be completely transparent about my own involvement with that particular test. You know, right now, we’re depending on a brain scan, a complicated, expensive brain scan to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease or a lumbar puncture. Well, both of those are inconvenient and expensive. What if we could diagnose Alzheimer’s disease with a blood test? And it looks like we’re going to be able to do that. It really looks like the blood test is now just as good as the spinal fluid test and the spinal fluid test is already approved for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. So I think we’re either right at the cusp or we’ve gotten over the hurdle of a blood test for Alzheimer’s disease. We’re just that close. Some of these blood tests are for diagnosis, that’s the one that’s in the news this week. Some of them, and there’s overlap here, also have to do with prognosis. So that when it changes, it also predicts that that person is likely to go on to get Alzheimer’s, not just providing diagnostic information. It gets to a certain level, that person has Alzheimer’s disease as far as we can tell. But if it’s going up, it also predicts that that person might get Alzheimer’s. And then there are other blood tests that are I think going to be really helpful. There’s a there’s a blood test for inflammation in the brain. There’s a blood test for degeneration of nerve cells in the brain. And I think we’re going to have a whole repertoire of blood tests that will help us define does this person have Alzheimer’s disease? What are the nuances of their disease? How much inflammation? How much TDP-43? And then what therapy would work best for them? We want to personalize therapy. We want to have precision medicine where the treatments we give to one person are for their disease. And the treatments we go to another person is for their individual disease. We’re getting closer and closer to that and the news about the new blood test this week, really exciting steps forward.

NANCY LYNN: Thank you. I learned something. I had no idea that there was such a range that the blood tests will be able to show. And I think I wanted to ask the audience, the whole area of AI and diagnostics, you know, things that can predict whether you’ll get Alzheimer’s, through language or through the way you walk or move. I think it’s a fascinating topic and if you are interested in us doing a program about this future technology, some of them are not so future in fact, just put a yes in the chat so I can gauge your interest on that. And, we’ve got 5 min left. Michael, can you ask your question briefly? Because I have one question I really want to pose at the end. Go for it, Michael.

MICHAEL: Sure. You touched on the blood test. Blood tests are usually very cheap for most other things today. Could you expand on why the blood test for dementia is still so expensive? Is there anything that they’re utilizing? Or is it just because it’s new? It’s costing, I mean, I think they’re costing around $500, $600, which is still very expensive for a blood test.

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Yes, thank you for that, Michael. So I’m not up on the costs. I think the $500 to $600 range is for the APOE gene test. I think it will come down as we have competitors. And I just don’t know what the new like, pTau test, that’s one that’s in the news, the GFAP test, that’s one that has inflammation. I just don’t know what they’re going to run. From my point of view, if it has to be done by a special technique called mass spectrometry, that’s expensive because it cannot be, it’s not really scalable. So you have to have a whole bunch of machines. You can’t just do it with robotics and all of that. Or you can’t completely do it with robotics. But if it can be done with simpler techniques, or just no reason it can’t be a cheap test, and should be a cheap test. We want to get these tests not only to more people in the United States, this is the global problem, right. We want the people in Thailand, Malaysia, you know, wherever to be able to have these blood tests and for us to be able to help them. And that’s a cost-related issue and we have to bring these costs down.

NANCY LYNN: Yeah, that’s terrific. And, thanks for asking that, Michael. And coverage is another huge topic that will for all things Alzheimer’s related that we’ll have to get to. And I’m going to mention again that one of the companies that offers these blood tests, C2N, that’s doing a lot of research in this area. A lot of those principal investigators were funded by BrightFocus Foundation early in their careers and again through the middle of their careers. So we’re always thrilled to see the scientists that we’ve funded making these breakthroughs. So it’s double excitement for us. I’m going to ask one question and I do hope you’ll come back because I haven’t, I don’t think I’ve gotten through half of the ones that I pulled. But I would like to ask as we close on behalf of Aaron from Austin, Texas, do you expect a treatment that stops the progression in the next 10 to 15 years? Look at all of these drugs in the pipeline and that big circle and those three circles. Do you expect a treatment that stops the progression in the next 10 to 15 years, not to put you on the spot or anything.

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Yeah, well, I’m glad to be put on this spot and it’s a good question. It’s something I think about all the time. And I’m going to go out on the limb and say yes. That stops the progression I think is a reasonable goal. People sometimes say cure Alzheimer’s disease. I doubt that that is actually reasonable, but can we stop its progression? We’re 30% of the way right now and of course some patients are way above that 30% and some below. So if we take those patients who are way above, try to understand that better, add a second drug to that, maybe a third drug will be necessary, I think that the likelihood that we’re going to be able to essentially arrest the progression is really high and that would certainly be our goal.

NANCY LYNN: That is so exciting. And, I want to thank you, Dr. Cummings, for being with us today. And thank you, Margaret, and thank you to all of you for participating. I noticed, you know, we’ve had over a hundred people on who stayed on the entire time, and I know there’s probably double that on Vimeo. If your questions were not answered today, you can email me. I know I put my email in the chat, but you might get a quicker response from reply@brightfocus.org, but we will respond and if necessary, we’ll forward the questions to Dr. Cummings and have him respond. We will be sending after, in about a week or two, this episode to everybody that registered. We can also provide you with free publications if you request them. There’s a phone number here and the email of info@brightfocus.org. We’re happy to provide free information for all of you. And resources for all the episodes are available at BrightFocus.org/ZoomIn and on BrightFocus’ YouTube channel.

And our next episode is with Dr. Marwan Sabbagh, who Dr. Cummings knows quite well. And we’ll look at what are the stages of Alzheimer’s dementia. And I find that fascinating because if you do an internet search on stages of Alzheimer’s, you will learn that there are three, no there are five, no there are seven, now there’s nine and what does it all mean and why are we trying to put them in stages so I’m loving the concept of this episode. So thank you, Dr. Cummings, and thank you to everyone. We’ll wrap it up right now. I hope you all have a great week and I’m so excited with, Dr. Cummings, with your final answer there. For those of us who have been doing this for myself about 15 years and I think a lot of people in field a lot longer, it’s just incredible to be able to finally be answering with some positives.

DR. JEFFREY CUMMINGS: Thank you so much for including me.

NANCY LYNN: Thank you. Thanks everybody. Have a wonderful day. Good to see you all again and we hope to see you next month.

BrightFocus Foundation is a premier global nonprofit funder of research to defeat Alzheimer’s, macular degeneration, and glaucoma. Since its inception more than 50 years ago, BrightFocus and its flagship research programs—Alzheimer’s Disease Research, Macular Degeneration Research, and National Glaucoma Research—has awarded more than $300 million in research grants to scientists around the world, catalyzing thousands of scientific breakthroughs, life-enhancing treatments, and diagnostic tools. We also share the latest research findings, expert information, and resources to empower the millions impacted by these devastating diseases. Learn more at brightfocus.org.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is a public service of BrightFocus Foundation and is not intended to constitute medical advice. Please consult your physician for personalized medical, dietary, and/or exercise advice. Any medications or supplements should only be taken under medical supervision. BrightFocus Foundation does not endorse any medical products or therapies.

About 25% of people carry one copy of the APOE4 gene, the strongest genetic risk factor for developing Alzheimer’s. Dr. Eric M. Reiman explains what genetic testing can—and cannot—tell you, including why APOE4 signals increased risk but does not mean a definite Alzheimer’s diagnosis.

Learn about the treatments landscape for Alzheimer’s in 2026 and beyond.

A leading neurologist answers your most common questions about what Leqembi and Kisunla can realistically do, including effectiveness, safety, eligibility, infusion logistics, cost, and access.

Join Dr. Joshua Grill as he shares details about the AHEAD Study.

Although there is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease, certain treatments can help control or delay its symptoms, particularly in the early stages of the disease. Talk to your physician to see if these medications are right for you.

Every Donation is a Step Forward in the Fight Against Alzheimer’s

Your donation powers cutting-edge research and helps scientists explore new treatments. Help bring us closer to a cure and provide valuable information to the public.

Donate Today