What Is "Healthy" Sleep and Why Is It Important for Alzheimer's and Other Diseases?

A BrightFocus Q&A with Sleep Expert Brendan Lucey, MD

Written By: BrightFocus Editorial Staff

A BrightFocus Q&A with Sleep Expert Brendan Lucey, MD

Written By: BrightFocus Editorial Staff

Sleep frequently comes up as a factor in defending against Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other forms of neurodegeneration as an activity that can boost healthy aging. Research has pointed to regular nightly “deep sleep” as something the brain depends on to flush itself of waste material and toxins, including excess amyloid-beta (Ab) protein, and to break down and dispose of Ab plaques that are seen in early AD. Researchers are exploring whether sleep may have the same rejuvenating impact for other neurodegenerative diseases of mind and sight.

On the other side of the coin, very recent research funded by BrightFocus has shown an association between excessive daytime napping and the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. [Read more about that research here.] While napping can be a healthy routine for many, the recent findings provide some of the first evidence that a two-way relationship exists between sleep and the risk of developing AD. In other words, while AD was already known to disrupt sleep, data now also show that the absence of healthy sleep (which is perhaps reflected in excessive napping) can be a contributor to AD’s development. For many, that’s a scary thought.

To explain what healthy sleep is and examine the ways in which a chronic lack of healthy sleep can damage the brain, we’ve turned to an expert, Brendan Lucey, MD, an associate professor of neurology specializing in sleep medicine at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, MO. Dr. Lucey both treats sleep disorders and conducts research into the relationships between sleep, patterns of Ab deposition, and Alzheimer’s. He’s a member of the BrightFocus Alzheimer’s Disease Research (ADR) Scientific Review Committee and a former ADR grantee.

BrightFocus: We are so fortunate to be able to discuss sleep with you! How long have you been a sleep clinician-researcher, and what led you to this field?

Dr. Lucey: I have practiced sleep medicine since 2009 and actively studied the relationship between sleep and Alzheimer’s disease since 2012. The importance of sleep to health and disease initially attracted me to the field. Sleep disturbances have been associated with a wide number of health problems, including metabolic problems like diabetes, heart disease, and Alzheimer’s disease. I was struck by how important sleep is (we devote a third of our lives to it!) yet we don’t fully understand its function. We also have many effective therapies to improve sleep and that is very satisfying as a physician.

BrightFocus: Does the phrase “a healthy night’s sleep” still ring true, and what’s meant by that?

BrightFocus: Does the phrase “a healthy night’s sleep” still ring true, and what’s meant by that?

Dr. Lucey: To me, a good night’s sleep or a healthy night’s sleep is best measured by how one feels during the day and is affected by many factors. For instance, we need to allow enough time to sleep, have a good sleep environment that is dark and quiet, treat any medical problems that may affect sleep at night, and avoid sleeping too much during the day. Any of these factors could lead to a bad night’s sleep. In addition, many of these factors change with normal aging. Napping is more common with increasing age and may not be a sign of a sleep problem. I often ask patients if they feel sleepy during the day or are unable to do what they want or need to do during the day. Napping may be the cause of sleep problems if a person is fragmenting their sleep by sleeping more during the day but less at night. Or napping may be a sign of problems with sleep overnight.

BrightFocus: How does one “study” sleep in a lab? Likewise, how do you diagnose and treat patients in the clinic for sleep disorders?

Dr. Lucey: During an overnight sleep study in the lab, patients are monitored with many sensors. There are sensors to measure brain waves for sleep staging, airflow through the nose and mouth, breathing effort, blood oxygen levels, heart rhythms, and leg movements. Using these sensors, we can determine if a patient is asleep or wake, what stage of sleep they are in, and if there are abnormalities of breathing, movements, or behaviors during sleep. Sleep studies in the lab are mainly used to diagnose specific sleep disorders like sleep apnea.

BrightFocus: Is there such a thing as “bad sleep? In other words, sleep occurs in several phases that relate to underlying brain activity —are some phases more important, or easier to obtain, than others?

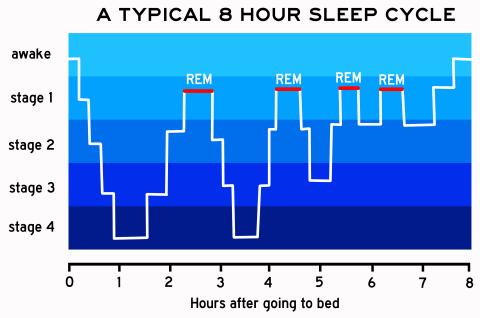

Dr. Lucey: During normal good quality sleep, we sleep long enough to cycle through different sleep stages. There are four types of sleep stages. Non-rapid eye movement sleep stage 1 or drowsiness is usually the first stage of sleep, followed by stage 2, and then deeper stage 3 or slow-wave sleep. Finally, we enter rapid eye movement or REM sleep. Throughout the night, we cycle between these stages with more REM sleep later in the night. If something is disrupting sleep, such as breathing events from sleep apnea, we don’t have enough time for our sleep to consolidate and get into the deeper stages. The analogy I like to use is a stone skipping across a pond: you are hitting the light stages of sleep (non-rapid eye movement sleep stages 1 and 2) near the surface but not getting to the deeper sleep stages (slow wave sleep and REM sleep).

BrightFocus: If the goal is to experience all phases of sleep in approximately 7-9 hours each night, what interferes with that in the normal aging process or the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease?

Dr. Lucey: There are many changes that occur during normal aging that may promote sleep disturbances. For example, time in slow wave sleep decreases with age and this is more in men than women and there is more wake time after sleep starts. There are also many changes that occur with aging, such as more medical problems and more medications, that may disrupt sleep. A major challenge for the field right now is how to know if changes in sleep are due to normal aging or if they are due to early Alzheimer’s disease or another factor. This is an area of on-going research, and a very challenging question to answer.

BrightFocus: What’s the impact on the brain when there are chronic deficits in certain types of sleep, including non-REM sleep?

Dr. Lucey: Chronically-disrupted sleep has multiple impacts on the brain and overall health, including problems with metabolism, mood, thinking, and heart function. Chronic sleep disturbances may lead to poor attention that makes it harder to remember things or increase accidents.

BrightFocus: Can people “train” themselves to become better sleepers? What are some of the changes that are often required?

Dr. Lucey: There are many steps that people can take to improve their sleep—they can allow themselves enough time to sleep, maintain a regular sleep schedule with sleep at night, avoid light exposure at night, and have a routine when getting ready for bed. Further, I recommend people see their doctor if they suspect a sleep disorder, such as sleep apnea or restless legs syndrome, in order to be evaluated and treated.

BrightFocus: Is napping “bad” for people? Recent, highly publicized research has pointed to an association between frequent daytime napping and increased risk for AD. However, can daytime napping sometimes be justified and even beneficial? What are some signs it may be excessive and becoming a problem?

Dr. Lucey: Napping is not always “bad” for people. Daytime napping may be needed in the setting of an illness or normal aging. A short nap during the day is normal for older adults. I think it is important to consider how people are sleeping during the night and how they are functioning during the day. For instance, if an older adult is getting an adequate amount of sleep during the night, 7-8 hours for example, and can do all of the activities throughout the day before and after their nap without feeling drowsy, then there is likely not a problem. However, if napping is occurring throughout the day, drowsiness is impairing daytime function before or after the nap, or nighttime sleep is fragmented, then there may be a problem with sleep. There are multiple reasons why older adults could have trouble sleeping at night and increased napping during the day. The number of older adults with sleep apnea increases with age, for instance. Medications could disrupt sleep, even indirectly. An example of this might be a person taking a diuretic for heart problems right before sleep and then they wake up throughout the night to urinate.

BrightFocus: What do we still need to learn about sleep and Alzheimer’s? Any exciting new research directions and/or potential treatment strategies?

Dr. Lucey: We still have a lot to learn about sleep and Alzheimer’s disease. Major questions in the field are: do sleep disturbances increase the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease?; are sleep disturbances a marker for the changes in the brain we see with Alzheimer’s disease?; or, is it both? We already have a lot of evidence that sleep disturbances are associated with an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease and that sleep disturbances occur in asymptomatic individuals without problems with thinking or memory but who have early changes in the brain from Alzheimer’s disease. However, the timing and sequence of changes in sleep and Alzheimer’s disease are not fully known. Potentially, sleep could be used as a marker to assess a person’s risk of Alzheimer’s disease and response to a treatment. Sleep may also be a marker for intervention, but a lot more work is needed before we are prescribing sleep interventions to prevent or delay Alzheimer’s disease.

BrightFocus Foundation is a premier global nonprofit funder of research to defeat Alzheimer’s, macular degeneration, and glaucoma. Since its inception more than 50 years ago, BrightFocus and its flagship research programs—Alzheimer’s Disease Research, Macular Degeneration Research, and National Glaucoma Research—has awarded more than $300 million in research grants to scientists around the world, catalyzing thousands of scientific breakthroughs, life-enhancing treatments, and diagnostic tools. We also share the latest research findings, expert information, and resources to empower the millions impacted by these devastating diseases. Learn more at brightfocus.org.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is a public service of BrightFocus Foundation and is not intended to constitute medical advice. Please consult your physician for personalized medical, dietary, and/or exercise advice. Any medications or supplements should only be taken under medical supervision. BrightFocus Foundation does not endorse any medical products or therapies.

Every Donation is a Step Forward in the Fight Against Alzheimer’s

Your donation powers cutting-edge research and helps scientists explore new treatments. Help bring us closer to a cure and provide valuable information to the public.

Donate Today