Learn about the most common type of glaucoma that accounts for 70 – 90 percent of all cases.

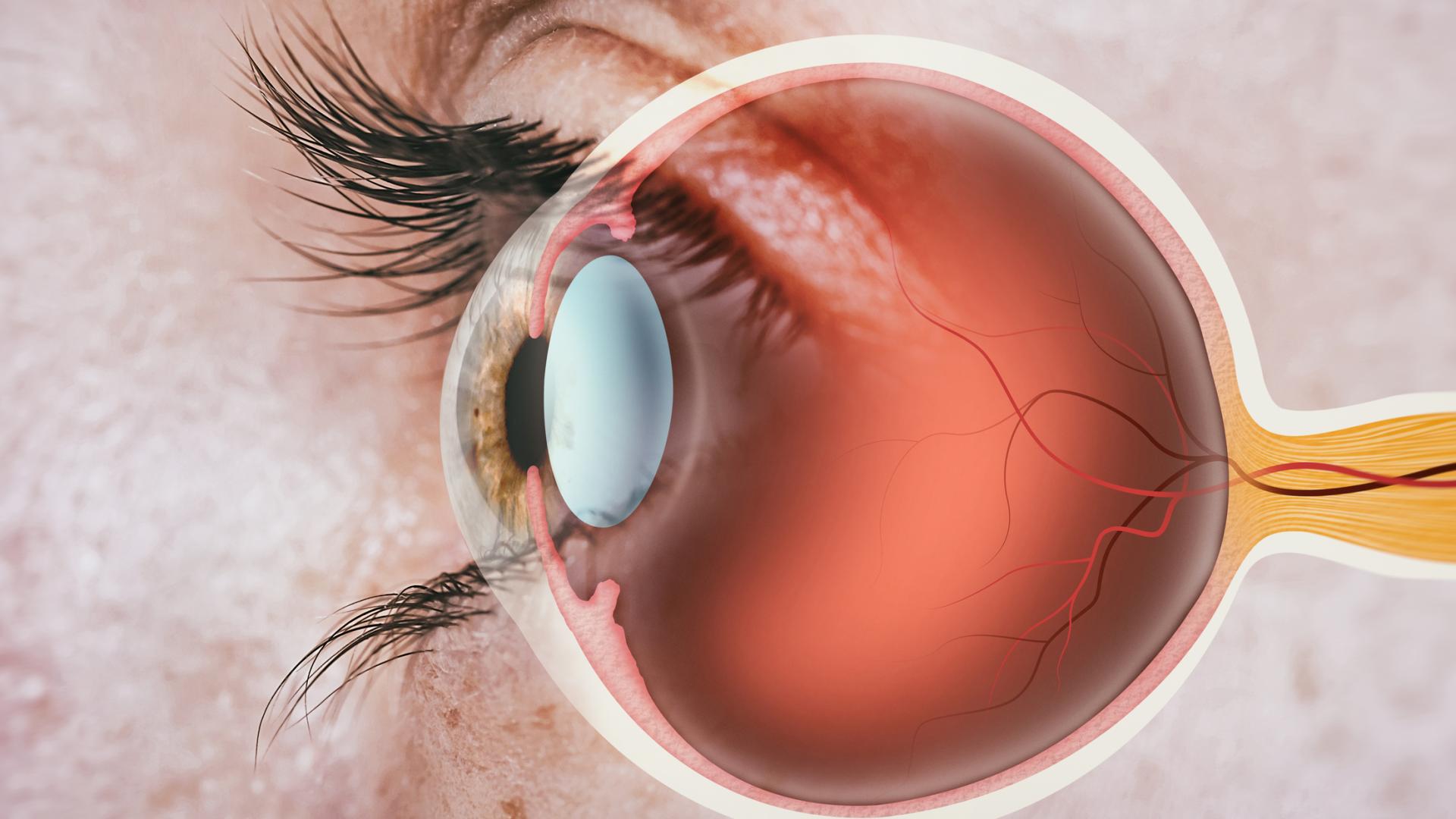

Glaucoma is a group of eye diseases in which the optic nerve degenerates. The optic nerve transmits all of the visual information from the retina, the light-sensing tissue of the eye, to the brain. The damage to the optic nerve is generally thought to be irreversible, although much basic research is being performed to determine if regeneration of the optic nerve is possible.

Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG), the most common form of glaucoma in the United States, is different from other glaucomas in that the drainage angle is in an “open” configuration, and there are no other causes for the glaucoma identified (for example, glaucoma that occurs due to trauma or steroid use).

View a Video on Open-Angle Glaucoma

The “angle” referred to here is the angle between the iris, which makes up the colored part of your eye, and the cornea, which is the outer, transparent structure at the front of the eye. The angle is the location where the aqueous humor (the fluid that is produced inside the eye) drains out of the eye into the body’s circulatory system.

POAG is chronic, progressive, and occurs in both eyes, although one eye may have severe disease, and the other eye has very little or early disease. This is one of the reasons patients report no symptoms since the “good” eye can often compensate for the “bad” eye until the disease reaches very advanced stages.

Prevalence

In the United States, it is estimated that 2.7 million people, age 40 and older, have POAG, and your risk of the disease increases as you get older. Glaucoma is the leading cause of blindness in African Americans, who are three to four times more likely than Caucasians to have the disease.. Hispanics also have higher rates of POAG.

Risk factors

The risk factors for glaucoma include:

- higher eye pressure

- older age

- family history of glaucoma

- African race or Hispanic ethnicity

- thinner cornea

- lower ocular perfusion pressure (which is essentially the difference between blood pressure and eye pressure)

- type 2 diabetes

- severe myopia (nearsightedness)

We will discuss two of these risk factors in more detail below:

High Eye Pressure

While there is no doubt that high eye pressure plays an important role in the development of POAG, and that lowering eye pressure is our only proven treatment to slow the disease, there is no “magic number” of eye pressure that defines glaucoma. Each person has an individual eye pressure level that his/her optic nerve is able to withstand. Indeed, we know that there are plenty of patients, up to 40 percent, in whom eye pressure is never in the “high” range, yet they still have glaucoma. You may hear the terms “normal-tension glaucoma” or “low-tension glaucoma” to describe this situation. Although there is some controversy over these terms, the main point is that primary open-angle glaucoma does not require elevated eye pressure for its diagnosis.

Family History

Family history of glaucoma is an important risk factor. Several studies of large populations of patients have demonstrated that having a first-degree relative (parent, sibling, or child) with glaucoma increases the risk of having glaucoma. This is an important fact to remember because if you have glaucoma, it would be prudent to encourage your first-degree relatives (if children, when they are adults over 40), to have a comprehensive eye exam with an eye doctor.

Symptoms

Primary open-angle glaucoma generally has no symptoms, which is why it is often called the “sneak thief of sight.” This is especially true in early-to moderate-glaucoma, where the decrease in side (peripheral) vision is not noticed. Most patients do not have pain, even sometimes when the eye pressure is very high. In more advanced glaucoma, patients may notice difficulty with their peripheral vision, and may report difficulty with driving, “near misses,” or accidents. In very advanced glaucoma, the central vision is diminished, affecting reading, driving, and other activities that require good vision.

Diagnosis

An eye doctor will perform a comprehensive eye exam, including an eye pressure measurement and a dilated exam of your optic nerve and retina. He or she will examine your drainage angle using a special mirrored lens. As part of the evaluation, you will be asked to perform a test of your side (peripheral) vision. You may also have scans or photos of your optic nerves (sometimes called OCT, for optical coherence tomography). All of these tests help your eye doctor determine whether you have glaucoma, or are at risk of developing the disease. It is important to note that sometimes the diagnosis of glaucoma evolves over time when there are demonstrated changes from one exam to the next. In cases when the diagnosis is less clear, you may be diagnosed as a “glaucoma suspect.” You should always follow-up with your eye doctor because the diagnosis becomes more evident over time.

Treatment

Currently, we treat all glaucomas by lowering eye pressure. Lowering eye pressure has been proven effective by large clinical trials to slow the disease in patients with “high” eye pressures and “normal” eye pressures.

The treatments we currently have include medications, laser trabeculoplasty, and surgery (minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries, tube shunts, and trabeculectomy, for example). The good news is that much research is also underway to develop surgeries that have fewer risks, as well as treatments that do not depend on lowering eye pressure. The goal of treatment is to slow the disease so that glaucoma will not impact your vision-related quality of life and to do so without intolerable side effects. Therefore, it is important for you to review your specific situation with your eye doctor, and discuss treatment options and their risks and benefits.

About BrightFocus Foundation

BrightFocus Foundation is a premier global nonprofit funder of research to defeat Alzheimer’s, macular degeneration, and glaucoma. Since its inception more than 50 years ago, BrightFocus and its flagship research programs—Alzheimer’s Disease Research, Macular Degeneration Research, and National Glaucoma Research—has awarded more than $300 million in research grants to scientists around the world, catalyzing thousands of scientific breakthroughs, life-enhancing treatments, and diagnostic tools. We also share the latest research findings, expert information, and resources to empower the millions impacted by these devastating diseases. Learn more at brightfocus.org.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is a public service of BrightFocus Foundation and is not intended to constitute medical advice. Please consult your physician for personalized medical, dietary, and/or exercise advice. Any medications or supplements should only be taken under medical supervision. BrightFocus Foundation does not endorse any medical products or therapies.

- Disease Biology