Explore how researchers are recruiting the immune system to fight Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s disease continues to affect the lives of millions of Americans. As our elderly population increases, our need to help patients and caregivers cope with this illness will continue to escalate. Treatment of Alzheimer’s has already improved vastly as a result of a deeper appreciation of patients’ and caregivers’ needs, our growing evidence base for the importance of lifestyle choices, and the availability of medications specifically indicated for the treatment of this brain disease. The medications currently approved by the FDA, unfortunately, have modest benefits and do not modify Alzheimer’s fundamental disease process. Researchers continue to search for better medications that will supplement other treatment approaches. In the search for disease-modifying medications, intense interest has focused on how the immune system can be recruited into the fight against Alzheimer’s.

The Function of the Immune System

Our immune systems constantly protect our bodies from invasion by infectious agents. In addition, immune system components monitor changes in our bodies’ own cells, for example, by eliminating or limiting some cancers. The cells of the immune system include cells that produce antibodies and also cells that attack, poison, and scavenge invading organisms or our own damaged cells. As we age, the immune system becomes both less and more active.

Aging Immune Systems

The aging immune system responds less vigorously to some unfamiliar new provocations. This is thought to underlie, for example, the smaller production of new antibodies seen in older adults who are vaccinated. It may also help to explain the confusing but common clinical situation that occurs when an older adult with a potentially serious infection presents clinicians with a deceptively small fever or increase in disease-fighting white blood cells.

In some ways, though, the aging immune system also becomes more rather than less active. Our brains, which have a special immune system that is mostly separate from that of the rest of the body, are protected by specialized immune cells called microglia that attack various kinds of diseases with toxic substances, including inflammatory cytokines. These substances can produce collateral damage, killing brain cells, and some researchers think the brain’s powerful immune response to amyloid plaques (one of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s) explains the destructive effects of this brain disease.

Recruiting the Immune System to Fight Alzheimer’s

Since the 1990s, researchers have been exploring ways in which the immune system’s effects could be recruited into the fight against Alzheimer’s. Early experiments showed that rodents with Alzheimer’s-like plaques induced by genetic manipulation could be immunized against toxic amyloid beta, the protein that aggregates into Alzheimer’s characteristic plaques. Remarkably, these experimental immunizations were shown to decrease the amount of brain amyloid (“amyloid load”) in these rodents while also improving their cognitive functioning.

Two Approaches

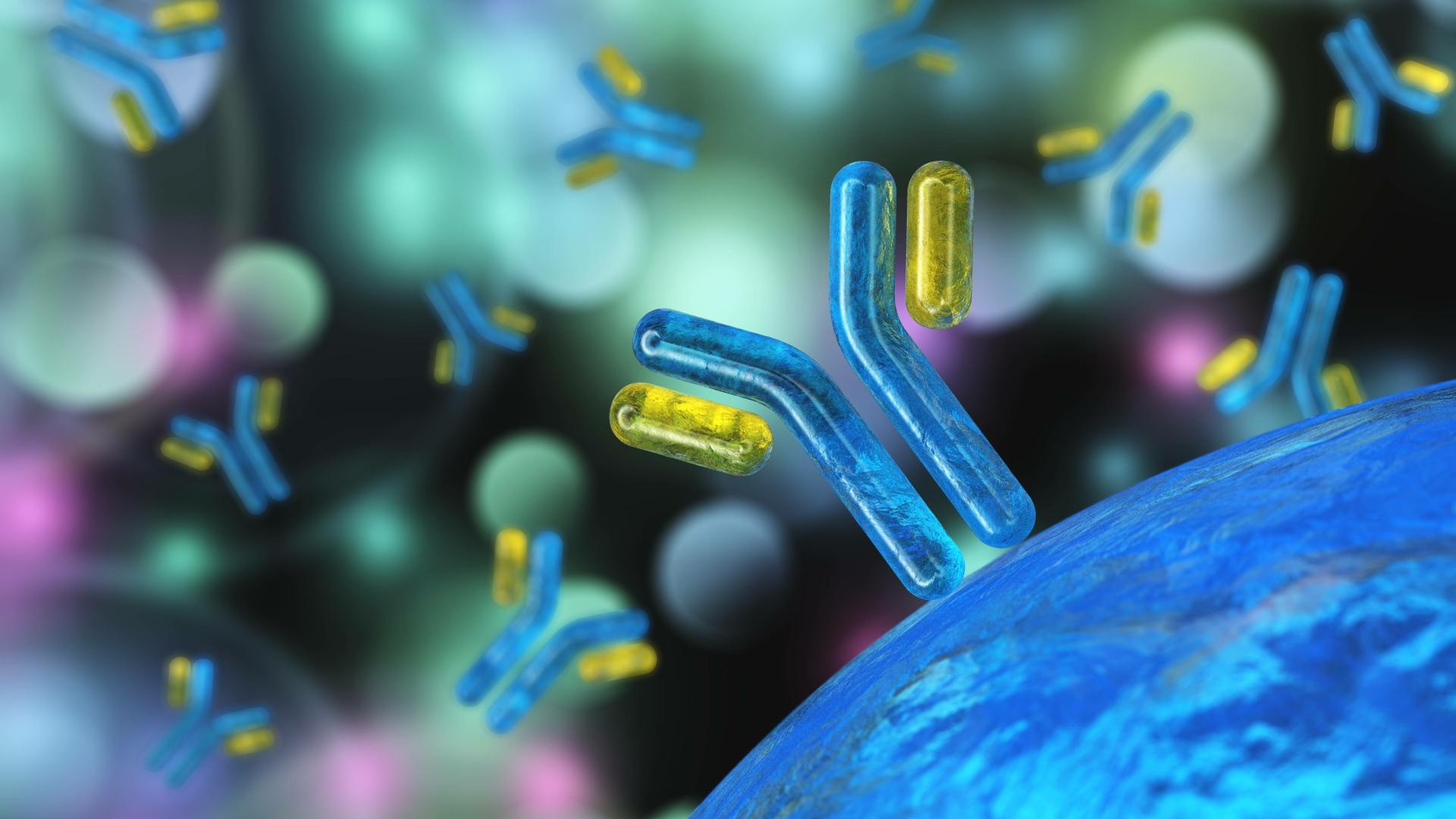

Immunotherapy, which is the use of immunity-enhancing techniques as a medical treatment, has taken two basic forms in the fight against Alzheimer’s. In active immunization, a fragment of amyloid beta or a related antigen is administered in order to stimulate a response of both antibody-based and cellular immunity. Passive immunization, by contrast, relies upon the intravenous injection of pre-formed antibodies into an animal for the purpose of boosting resistance to the aggregation of amyloid beta or helping the immune system remove amyloid beta already aggregated into plaques. Although only a small fraction of intravenously administered antibodies pass the blood-brain barrier and enter the brain, their significant effects indicate the potential value of this treatment approach.

Active immunization seemed initially to be the most promising method, because vaccination might induce long-term protection after a small number of relatively inexpensive treatments. Evaluation of the first widely tested human anti-amyloid beta vaccine, however, was stopped in 2002 because its effects included an unacceptably high rate (6%) of meningoencephalitis, a type of central nervous system inflammation that can be fatal. The hope for an Alzheimer’s vaccine has not been fully abandoned, however, and several new vaccines believed less likely to cause meningoencephalitis are currently in testing.

Passive immunization has appeared a safer treatment approach to many investigators, though it requires repeated infusions and accrues greater expense. Infusion of pooled IGG (gamma globulin) has not proved as effective as originally hoped, but many investigators regard the use of “monoclonal” antibody infusions as promising. Monoclonal antibodies are all of an identical structure, and they are designed to attack and help eliminate bbeta-amyloidin various forms. Bapineuzumab, an early member of this class of medications, was pushed to the sideline because of associated adverse effects: brain swelling (vasogenic edema) and focal bleeding (micro-hemorrhages, later termed amyloid-related imaging abnormalities or ARIA). Testing of solanezumab as a treatment for mild dementia, a monoclonal antibody that targeted smaller amyloid beta molecules circulating in the blood, was halted in 2016 when the medication failed to demonstrate efficacy in clinical trials. Other monoclonal antibodies, including aducanumab, gantenerumab, and BAN2401 have also been developed. Use of the newer agents is less frequently associated with brain swelling and focal bleeding.

Hope for Early Intervention

The proof of immunotherapy, ultimately, will be its ability to modify the course of Alzheimer’s. It would be fair to say at this point that both active and passive immunization against amyloid beta have been shown to reduce the brain’s amyloid load but not to produce significant cognitive benefits in patients with advanced Alzheimer’s. There is much greater hope, however, for the beneficial effects of early intervention. Findings suggest that passive immunotherapy at a very early stage may have significant clinical effects, and several large-scale trials are now underway to test the effects of passive immunotherapy in prodromal or early Alzheimer’s disease in early-stage human subjects whose diagnosis has been verified using PET amyloid scanning or cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Needless to say, the results of these trials are eagerly awaited by researchers, patients, and caregivers! We are already on the verge of possible FDA approval of one of the monoclonal antibodies as an Alzheimer’s disease treatment. On the basis of a re-analysis of data from trials of aducanumab, which was initially regarded as a failed treatment, Biogen submitted an application to the FDA for a treatment indication and the FDA’s decision is soon to be announced. It is likely that other immunotherapeutic agents will also be submitted to the FDA in the near future.

Summary

Immunotherapy is a powerful treatment approach that holds considerable promise for the future. Already it has improved the management of some serious cancers, and it may similarly improve our care of Alzheimer’s patients. Among the improvements of immunotherapy already being tested are the targeting of molecules other than amyloid beta, including disordered tau protein, and the development of safer and more effective antibodies. As the future unfolds, immunotherapy may be the first truly disease-modifying weapon in our efforts to reduce the devastating effects of Alzheimer’s.

About BrightFocus Foundation

BrightFocus Foundation is a premier global nonprofit funder of research to defeat Alzheimer’s, macular degeneration, and glaucoma. Since its inception more than 50 years ago, BrightFocus and its flagship research programs—Alzheimer’s Disease Research, Macular Degeneration Research, and National Glaucoma Research—has awarded more than $300 million in research grants to scientists around the world, catalyzing thousands of scientific breakthroughs, life-enhancing treatments, and diagnostic tools. We also share the latest research findings, expert information, and resources to empower the millions impacted by these devastating diseases. Learn more at brightfocus.org.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is a public service of BrightFocus Foundation and is not intended to constitute medical advice. Please consult your physician for personalized medical, dietary, and/or exercise advice. Any medications or supplements should only be taken under medical supervision. BrightFocus Foundation does not endorse any medical products or therapies.

- Industry News

- Treatments