The word “circadian” refers to bodily processes that recur on a daily cycle, such as sleeping. This article discusses why disturbances in circadian rhythms are common symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease.

Monica looked very upset as we talked about how difficult it had become to care for her husband, Alan*. Two years earlier, at age 74, Alan was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. He remained a gentle and loving man, but one difficult problem was getting worse. “The trouble begins every day around dinner time,” Monica said, “with Alan’s agitated behavior that just picks up steam throughout the evening! Alan wanders around the house all night, and I’m afraid he’ll start a fire or fall and hurt himself. I need my own sleep, but I’m afraid of what will happen if I don’t keep an eye on him. I try to keep him up during the day so he’ll sleep better, but I can’t stop him from napping! What can I do?”

Sleep and Alzheimer’s

Forty-five percent of people with Alzheimer’s report problems with sleep, and you can bet that this is a problem for 100 percent of their caregivers. Sleep problems have dramatic effects on patients and those who live with them. Disturbed sleep is one of the conditions that can endanger a person with Alzheimer’s. Night-time wandering can make institutionalization, for safety and caregiver quality of life, an earlier necessity.

The sleep problems of people with Alzheimer’s are a special type of insomnia which reflects the disease’s effects on every aspect of sleep. People with Alzheimer’s can have trouble falling asleep, trouble staying asleep, difficulty staying awake during the day, and unpredictable shifts between wakefulness and sleep that don’t fit into the usual daily cycle.

A Special “Clock” in the Brain

Studies of animals, humans, and postmortem brains have made clear much about what happens with normal and abnormal sleep. Much of the problem arises from the destruction of a special “clock” in the brain that tells us when to be awake and when to be asleep. This clock is responsible for setting “circadian rhythms.”

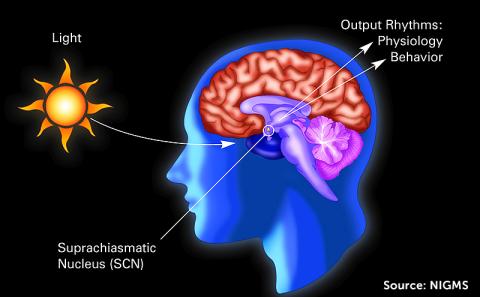

The word “circadian” refers to bodily processes that recur on a cycle that is approximately 24 hours (daily). The brain area that regulates circadian processes is a tiny region of the hypothalamus called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN). The hypothalamus is involved in the regulation of many of the body’s key processes.

The SCN communicates with other areas of the brain, telling your body when you should get sleepy or wakeful. The light you see and other brain signals, including melatonin from the pineal gland, keep the SCN in sync with the outside world. The SCN goes through a daily routine that requires it to make special proteins that combine, inhibit further protein production, and then self-destruct over the course of about 24 hours. The next day, the process starts all over again. Different parts of the hypothalamus coordinate with each other to increase alertness during the day and sleepiness at night.

A Clock Malfunction

People with Alzheimer’s are prone to develop sleep problems because the disease interferes with the SCN clock’s activity. β-amyloid buildup in the brain, one of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s, has been shown to interfere with normal sleep/activity patterns in rodents, and it is believed to have this effect in humans, too. In people with Alzheimer’s, SCN brain cells die during the course of the disease, and the loss of these cells sabotages normal regulation of the rest-activity pattern of daily life. Clinical dementia isn’t necessary for impaired sleep because changes in sleep have even been found in people who are cognitively normal but have increased amyloid deposits in their brains or have increased genetic risk for Alzheimer’s because of a higher-risk variant of the apolipoprotein E gene, called ApoE4.

Sleep and Cognition: A Vicious Cycle

To make matters even more complicated, there seems to be a reciprocal relationship between sleep problems and cognitive problems in Alzheimer’s. In other words, poor sleep is not only a result of Alzheimer’s, but it is also an aggravating contributor to further decline. Deep sleep, it turns out, is essential to brain health as it is during this time that β-amyloid is cleared from the brain through the activity of the brain’s internal cleaning service, the glymphatic system.

Improving Sleep

Knowing what we do about the SCN and sleep problems in Alzheimer’s should help us design treatments that are more effective for this particular type of insomnia.

Changing Sleep Habits

One important step in helping people with Alzheimer’s and poor sleep is to work on improving sleep habits and scheduling. Researchers have tried to improve activity-rest coordination in people with Alzheimer’s, for example, by focusing on the right kind of activity during the day and good sleep hygiene at night. Limiting naps during the daytime and limiting light and noise that disrupt sleep at night may help some people.

Bright Light Therapy

Bright light therapy, which stimulates the pineal gland and helps regulate melatonin secretion, has shown beneficial effects in some studies, reducing agitation and improving mood and appetite. The beneficial effect of bright light therapy on sleep itself, unfortunately, remains uncertain.

Medications

Melatonin treatment seemed to improve sleep in one study of people with Alzheimer’s, but so far, there isn’t strong evidence that it also helps cognitive functioning. Later in the course of the disease, the SCN is more damaged, and the brain may be less sensitive to melatonin’s effects. Melatonin combined with bright light therapy may be more helpful than melatonin alone for some patients.

Sleeping pills such as benzodiazepines are not generally recommended because they can increase fall risk, daytime sleepiness, and confusion — but the sedating antidepressant trazodone may help prolong sleep time for some people with Alzheimer’s without adding as much risk as the benzodiazepines do.

Help for Alan

Although we don’t yet know how to repair a damaged SCN, Alan’s circadian rhythms and sleep schedule were helped by some basic changes in sleep habits. A regular schedule for arising and retiring, limitation of bright light exposure (such as the computer screen or smartphone) in the period before scheduled sleep, reduction of caffeine and other stimulants, bladder-emptying just before bedtime, and sparing use of trazodone all helped Alan stay in bed more consistently at night. A bed alarm designed to alert Monica when Alan left his bed helped Monica feel safer in her caregiver role.

*Patients described in my blogs are composite vignettes so as to protect individual anonymity and confidentiality.

About BrightFocus Foundation

BrightFocus Foundation is a premier global nonprofit funder of research to defeat Alzheimer’s, macular degeneration, and glaucoma. Since its inception more than 50 years ago, BrightFocus and its flagship research programs—Alzheimer’s Disease Research, Macular Degeneration Research, and National Glaucoma Research—has awarded more than $300 million in research grants to scientists around the world, catalyzing thousands of scientific breakthroughs, life-enhancing treatments, and diagnostic tools. We also share the latest research findings, expert information, and resources to empower the millions impacted by these devastating diseases. Learn more at brightfocus.org.

Disclaimer: The information provided here is a public service of BrightFocus Foundation and is not intended to constitute medical advice. Please consult your physician for personalized medical, dietary, and/or exercise advice. Any medications or supplements should only be taken under medical supervision. BrightFocus Foundation does not endorse any medical products or therapies.

- Brain Health

- Lifestyle

- Risk Factors